Your Social Security Number: The 9-Digit Evolution

"There are downsides to everything; there are unintended consequences to everything."

—Steve Jobs

Introduction

Imagine living in our country 100 years ago: no televisions, microwaves, iPhones, laptops, credit cards, or ATMs—and no Social Security numbers (SSNs). Definitely, major changes have evolved with inventions and advancing technology. And there's a story to go with each change.

Among the many changes over the years, the evolution of the SSN's usage ranks near the top. But what's the story on how the SSN became an almost universal identifier in the United States? Is there a downside to this?

The Beginning

The story of the SSN starts during the Great Depression. Millions of people were struggling without jobs or income. The elderly were hit especially hard. This triggered a concern for the future of the elderly.

In 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act. Although the Act was passed during the Great Depression, it was designed to ensure the future economic security of individuals and did not address the immediate economic problems of the Great Depression.

Social Security's primary original purpose was to provide financial benefits to people over age 65. Upon retirement, people who were no longer working would receive monthly retirement benefits or Social Security income. Benefit amounts would be based on a person's earnings in covered employments.1 Monthly benefits were scheduled to begin in 1942.2

The Social Security Act required a payroll tax for both employees and employers based on earnings. As a result, the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) was enacted in 1935. It gave the responsibility of collecting payroll taxes to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).3 Named for the Act, these taxes are commonly called "FICA taxes." Employers began deducting payroll taxes from workers' wages in January 1937.4

Recordkeeping

To carry out the Social Security Act, the Social Security Board was created. (This was later renamed the Social Security Administration.5) One of its first tasks was setting up a recordkeeping system. The earnings of each individual had to be tracked beginning in 1937. It was obvious that using a person's name wouldn't work. Can you imagine the difficulty in keeping accurate earnings records for those with common names such as John Smith or Jane Jones? Several tracking plans were considered, such as using a combination of letters and numbers or using fingerprints.

The chosen solution was to use a 9-digit number divided into three parts: area number, group number, and serial number. The first three digits, the area number, represented the state in which the SSN was issued. (See boxed insert, "Sample SSN Area Numbers and Locations.") Generally, lowest area numbers were given to people on the East Coast, with increasingly higher numbers given going westward. However, there were exceptions. For example, a worker could apply in person for an SSN in any Social Security office, and the area number would reflect that office's location, regardless of the worker's residence.6 The next two digits, the group number, were determined by issuing numbers in groups to issuing offices. The last four digits, the serial number, represented the order within each group.

But issuing SSNs was a work in progress. While the details of the Social Security Act were being worked out, the U.S. Postal Service accepted the responsibility of issuing SSNs. At this time, there were approximately 45,000 post offices across the nation. From these, 1,074 post offices were called on to be "typing centers" to issue Social Security cards and SSNs. In November 1936, the first SSNs were issued by these typing centers and thousands of people were given their 9-digit number. The post office did not keep the records. They were sent to the main Social Security Office in Baltimore, Maryland.7 Within about six months, approximately 35 million SSNs had been issued.8

By mid-1937, Social Security field offices were able to take over. In 1972, after computer-based systems became available, all SSNs were issued exclusively from the central Social Security Administration (SSA) office in Baltimore, Maryland. With this change, the area number was assigned based on the ZIP code of the mailing address provided on the application.9

And it all changed again in 2011 when the SSA began randomly assigning SSNs. This "randomization" shares the pool of available SSNs nationwide.10 There is no geographical significance to the first three digits of SSNs issued after this date. Randomization extends the quantity of SSNs available for the future. For example, a state with an increasing population will need more SSNs in the future. A state with a decreasing population won't need all that it was allotted. By sharing the available SSNs nationwide, the pool of numbers will last longer. The new system does not affect previously issued SSNs and only applies to new applications for SSNs.11

SSN Usage

The use of SSNs has increased over the years. The trend began in 1943 when federal agencies were required to use SSNs for identifying individuals in any new record system.12 As computer technology evolved in the 1960s, the expansion soared. Today, a SSN is required for opening a checking or savings account, securing a loan, finding employment, filing taxes, renting an apartment, receiving medical services, completing credit and insurance applications, and the list goes on.

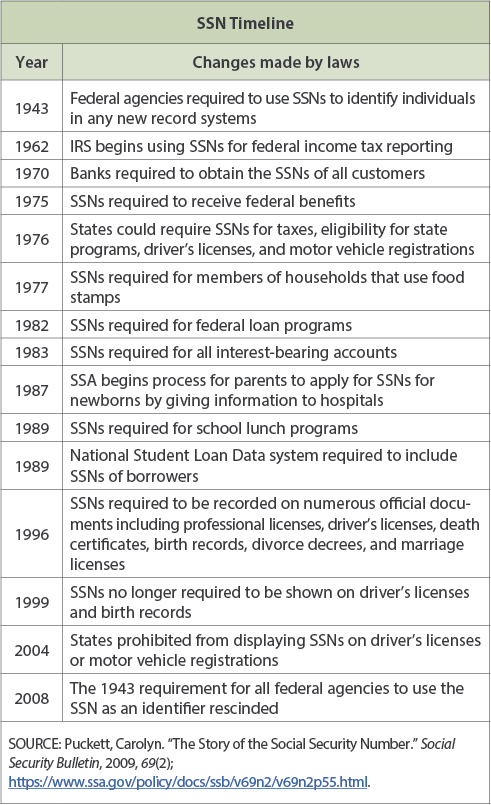

Laws have increased the use of SSNs. (See boxed insert, "SSN Timeline.") For example, the IRS began using SSNs for federal income tax reporting in 1962. And the IRS requires banks, insurance companies, and employers to collect SSNs for income and tax-related purposes. Legislation also requires low-income families to provide SSNs of all adult household members to apply for school lunch programs. These and many other laws have supported the use of SSNs as an identifier.

The Social Security Card and SSN

To get an SSN, a person must fill out the Form SS-5 application for a Social Security card. The application asks for date of birth, place of birth, and full name given at birth. The form also asks for the mother's maiden name and parents' SSNs, among other things.13

From the beginning, people were concerned about how the personal information collected for an SSN would be kept confidential. The SSA has continued to protect the information and safeguard the integrity of the SSN.

The Social Security card has had over 50 designs to date and all versions remain valid. As the use of SSNs has expanded, changes have been made in the card's design to prevent counterfeiting. Today, a counterfeit-resistant version is now used for both original and replacement cards.14

Identity Theft

Your SSN is required frequently, and that means it's stored in many places. But can you count on everyone who collects your SSN for business purposes to protect it properly? Probably not.

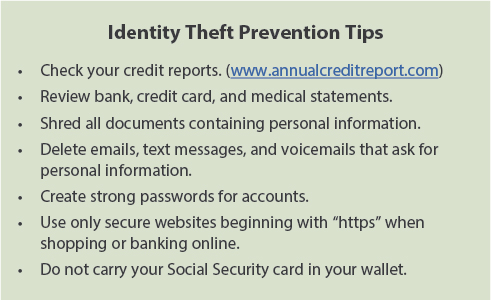

The SSN is a key piece of information used to commit identity theft. SSNs have become increasingly available to identity thieves, at least in part because they are so widely used as identifiers. Criminals can steal SSNs from workplace records, mail, wallets, or public records. And high-tech ways such as phishing or hacking into a computer database are increasingly a concern.

When criminals steal an SSN and the victim's identity, they can do a lot of damage. They can use an SSN to file an income tax return in your name to steal your refund. They can use it to facilitate opening new accounts, gain access to existing accounts, commit medical identity theft, seek employment, secure a payday loan, or obtain government benefits.15 A stolen SSN can open ways for criminals to access other personal information and cause a lot of problems that may show up on your credit report. (See boxed insert, "Identity Theft Prevention Tips.")

Creation of New Markets

In recent years, high-profile data breaches have increased the concern for protecting personal data—with the SSN rating near the top in priority. Community organizations and businesses conduct "shred days" for safely destroying documents containing personal data. Office supply stores have responded by stocking shelves with crisscross shredders.

The demand for greater protection has created new markets as millions of U.S. consumers spend billions of dollars buying products and services that claim to protect personal data. Personal data-protection businesses that offer online subscription services, advertise free trials, and provide automatic direct billing of monthly fees for different coverage plans have sprung up. The choices continue to increase. There are plans designed to monitor credit card, debit card, and bank accounts. Some plans specifically advertise "Identity and Social Security Number Alerts."

In response to the concern for protecting personal data, both government and business SSN usage has decreased in recent times. For example, laws have changed to prohibit using SSNs on driver's licenses or requiring them on birth records. These actions are a response to the identity theft concern—and change will continue.

Conclusion

In the beginning, when President Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act, the purpose of the SSN was identification for accurate recordkeeping. Accurate records of workers' earnings were necessary for administering benefits under the Social Security program. That is still the primary purpose for the SSN.16

But it has evolved into so much more. Because an SSN is convenient, reliable, unique to each individual, and in many cases required by law, it has become an important 9-digit number that follows a person throughout a lifetime. The age of technology has increased the benefits of its usage while increasing the need for security. Identity theft is a downside to the increased use of SSNs, and new markets have opened a new industry for identity protection. Speculation can be made that this evolution is an unintended consequence of the original Social Security Act that President Roosevelt could never have envisioned.

Notes

1 Covered employment initially covered only about half the jobs in the country, which were in commerce or industry. See Martin, Patricia and Weaver, David A. "Social Security: A Program and Policy History." Social Security Bulletin, 2005, 66(1); https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v66n1/v66n1p1.html.

2 Martin, Patricia and Weaver, David A. "Social Security: A Program and Policy History." Social Security Bulletin, 2005, 66(1); https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v66n1/v66n1p1.html.

3 Disability Benefits Center. Federal Insurance Contributions Act; https://www.disabilitybenefitscenter.org/glossary/federal-insurance-contributions-act.

4 Martin and Weaver, 2005. See footnote 2.

5 In 1946, the Social Security Board became the Social Security Administration (SSA); https://www.ssa.gov/history/orghist.html.

6 Puckett, Carolyn. "The Story of the Social Security Number." Social Security Bulletin, 2009, 69(2); https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v69n2/v69n2p55.html.

7 Social Security Administration. "Social Security Numbers: The First Social Security Number and the Lowest Number"; https://www.ssa.gov/history/ssn/firstcard.html.

8 Puckett, 2009. See footnote 6.

9 For earlier-issued numbers, the area number represents the state of birth. The following link will tell what area numbers go with each state: Social Security Administration. "Social Security Number Allocations." Business Services Online (BSO); https://www.ssa.gov/employer/stateweb.htm.

10 Social Security Administration. "Social Security Number Randomization." Business Services Online (BSO); https://www.ssa.gov/employer/randomization.html.

11 Social Security Administration. "Social Security Number Randomization Frequently Asked Questions." Business Services Online (BSO); https://www.ssa.gov/employer/randomizationfaqs.html.

12 Puckett, 2009. See footnote 6.

13 Form SS-5 can be found at http://www.socialsecurity.gov/online/ss-5.pdf.

14 Puckett, 2009. See footnote 6.

15 Federal Trade Commission. "Security in Numbers: SSNs and ID Theft." Federal Trade Commission Report, December 2008; https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/security-numbers-social-security-numbers-and-identity-theft-federal-trade-commission-report/p075414ssnreport.pdf.

16 Puckett, 2009. See footnote 6.

© 2020, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

Glossary

Credit report: A loan and bill payment history kept by a credit bureau and used by financial institutions and other potential creditors to determine the likelihood that a future debt will be repaid.

Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) tax: A tax or required contribution that most workers and employers pay. FICA is a payroll tax used to fund Social Security and Medicare.

Income: The payment people receive for providing resources in the marketplace. When people work, they provide human resources (labor) and in exchange receive income in the form of wages or salaries. People also earn income in the form of rent, profit, and interest.

Income tax: Taxes on income, both earned (salaries, wages, tips, commissions) and unearned (interest, dividends). Income taxes can be levied on both individuals (personal income taxes) and businesses (business and corporate income taxes).

Internal Revenue Service (IRS): The federal agency that collects income taxes in the United States.

Phishing: When someone attempts to get your personal information by pretending to work for a legitimate or legitimate-sounding organization, such as a bank or the government.

Social Security: A federal system of old-age, survivors', disability, and hospital care insurance that requires employers to withhold (or transfer) wages from employees' paychecks and deposit that money in designated accounts.

Social Security income: The monthly monetary amount received by retired workers who paid into the Social Security system while they worked.

Taxes: Fees charged on business and individual income, activities, property, or products by governments. People are required to pay taxes.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed