What Happens When Countries Increase Tariffs?

While the United States has been a longtime advocate of free trade, its trade policy has recently changed. In addition to exiting from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the United States has also begun raising tariffs on imports from specific countries and industries.

This essay investigates the potential impact of higher U.S. tariffs on the U.S. economy. To do so, we investigate the evolution of key macroeconomic variables following past episodes of tariff increases across a large number of countries. We identify episodes of tariff increases using import tariff data from the World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) over the period 1980-2006. We examine all episodes in which import tariffs increased by at least 3.5 percentage points in a year; we identify 16 such episodes.1

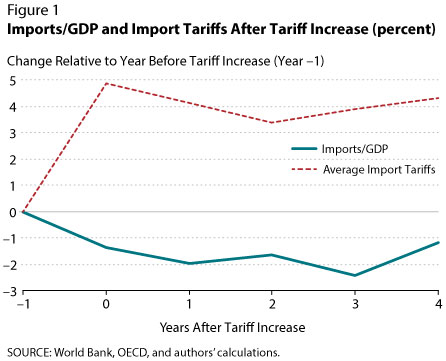

Figure 1 plots the evolution of average import tariffs and the average imports-to-GDP ratio from the year before the tariff increase (year –1) through the following 5 years.

First, we find that the almost 5-percentage-point average increase in tariffs is persistent: That is, tariffs remain persistently higher for at least 5 years. Second, the imports-to-GDP ratio decreases gradually, by close to 2.5 percentage points over the first 4 years after the tariff increase.

Next, Figure 2 plots the evolution of key macroeconomic variables—the average dynamics of GDP per capita, the investment-to-GDP ratio, and total annual wages—following these episodes.2 GDP per capita and total wages are expressed as percent deviations from trend.3

We find that GDP per capita and wages each fall by around 2 percentage points relative to trend over the first 2 years after tariffs increase.4 Moreover, the average investment-to-GDP ratio declines by approximately 1 percentage point after tariffs increase and the decline persists over the 5-year sample.

While these figures show that past tariff increases have been typically followed by large and persistent decreases in economic activity, this evidence does not necessarily mean that the higher tariffs caused these changes. It is possible that other economic events might have driven tariff increases and (slightly later) recessions.

Yet, a recent study by Barattieri, Cacciatore, and Ghironi (2018) does indeed suggest that higher tariffs produce these macroeconomic outcomes. In particular, using data similar to ours and a methodology that allows them to identify the causal impact of tariffs, they show that increases in protectionism lead to declines in GDP and higher inflation and have very little effect on the balance of trade (exports versus imports). Our findings are quantitatively similar to their panel-VAR (vector autoregression) estimates.

These findings suggest that previous unilateral tariff increases have reduced economic activity. Further research needs to be conducted to evaluate the potential impact of higher tariffs on the U.S. economy under the current economic conditions.

Notes

1 We focus on episodes in which average import tariffs increase by at least 3.5 percentage points, to ensure a sufficient number of episodes to conduct our empirical analysis. If a country experiences multiple such episodes, we use the first episode.

2 See Figure 2 note.

3 We detrend the data using the Hodrick-Prescott filter with smoothing parameter 6.25.

4 Specifically, the values reported for GDP per capita and wages are the difference between their deviation from trend in the given year and their deviation from trend in year –1.

Reference

Barattieri, Alessandro; Cacciatore, Matteo and Ghironi, Fabio. "Protectionism and the Business Cycle." NBER Working Paper No. 24353, National Bureau of Economic Research, February 2018.

© 2018, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed