How Does the Gig Economy Support Entrepreneurship?

"Not many jobs will allow a worker to just show up when they feel like it, and work only for as long as they choose to."

—Judith Chevalier, Economist1

Have you ever wondered where some of the most iconic American brands came from? Think of products such as Coca-Cola or Nike athletic shoes. Or think of convenient ways of doing business such as buying nearly anything online from Amazon.com or managing your calendar, photo collection, and media library using your iPhone. Well, many of these products and companies started with an individual who had a great idea and a willingness to work hard and take risks to turn that idea into reality. We call these people entrepreneurs.

Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurs develop new products and start new businesses. They recognize opportunities and the prospect of financial rewards. They enjoy working for themselves and will accept challenges. There are certainly risks for entrepreneurial activity: Entrepreneurs often risk their own money or borrow against their future earnings; they forgo other opportunities (say, taking a job as an engineer, nurse, or accountant) to pursue their dreams. Of course, chasing your dreams doesn't always pay the bills. So how do they make ends meet?

Enter the Gig Economy

For people who want to work for themselves, the gig economy provides some exciting opportunities. It is made up of companies whose business model usually involves a smartphone app that serves a key role in two-sided markets, matching people who want and will pay for a service with those who will provide a service for a fee. In fact, an app plays a key role in how these businesses function; it can make launching a new business a little easier because it takes care of many of the details that a small business would often have to do on their own, such as attracting clients, collecting fees, and compensating producers for the jobs they perform.

App-based ride-hailing businesses such as Uber and Lyft are some of the most widely known in the gig economy. Ride-hailing apps offer low barriers to entry because drivers use their own or rented cars to offer rides whenever they choose. These businesses offer workers true flexibility; there are no minimum hour requirements, so drivers can work however many hours they want to.

Making Ends Meet with Gigs

Entrepreneurs can both work in the gig economy and establish a new business at the same time. This enables them to smooth their income while they develop their product and work to get their business up and running; that is, they can supplement their income when their new business is slow. In fact, the vast majority of Uber drivers work only 8, 12, or maybe 15 hours a week driving,2 using these gigs to supplement their income from their startup or another job. So how do entrepreneurs balance working on their business venture and working their gig job?

Balancing Gig Work and Entrepreneurship

Let's again use Uber as an example. Research suggests that an Uber driver's willingness to work is related to the driver's reservation wage,3 which is the earnings level below which the person will not work. For example, if a worker's reservation wage is $25 per hour, then the worker will not accept work for less than that: Wages above $25 per hour result in surplus, so the worker will gladly take the work.

Consider an entrepreneur who just started a small business but also wants to supplement income while the product catches on, so she drives Uber when her schedule allows. Her reservation wage might be very high during hours in which her new business is open—say, $75 per hour. But her reservation wage might be lower in the evenings when she would otherwise be socializing or relaxing—say, $10 per hour. In this case, an entrepreneur would be less likely to drive Uber during regular business hours (9 a.m.-5 p.m.) and more likely to drive in the evenings and on weekends.

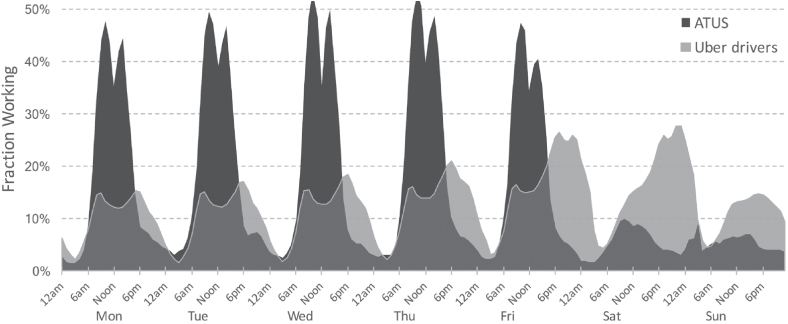

Comparison of Uber Drivers to Workers in the American Time Use Survey (ATUS)

SOURCE: Chen, M.K.; Rossi, P.E.; Chevalier, J.A. and Oehlsen, E. "The Value of Flexible Work: Evidence from Uber Drivers." Journal of Political Economy, December 2019, 127(6), pp. 2735-94; https://doi.org/10.1086/702171.

Data suggest the same pattern; that is, Uber drivers provide more rides outside of conventional business hours. The figure shows the working habits of employed males over 20 years of age surveyed in the American Time Use Survey (darker areas) and the working habits of Uber drivers (lighter areas). As suggested, Uber drivers put in more hours in the early morning, in the evenings, and on weekends.

Economist Judith Chevalier tells the story of being picked up in a very nice, very large car on a recent business trip. In addition to driving for Uber, the driver also ran a funeral service. When Chevalier asked her about her reasons for driving, the driver said, "If nobody dies, I drive. If somebody dies, I don't."4 Her answer shows that she knew her reservation rate and that she valued the extra work and wages to help smooth her income over time.

Conclusion

The gig economy supports entrepreneurship by providing entrepreneurs with opportunities to earn extra income. In fact, researchers suggest that the gig economy supports and encourages more entrepreneurial activity, finding an increase of 4-6% in new business registrations following the arrival of the gig economy in a city.5 In short, the gig economy provides services that people value, and it also has a spillover: It encourages entrepreneurial activity by supplementing and smoothing the income of entrepreneurs.

Notes

1 Madhusoodanan, J. "Gig Workers Value their Flexibility…a Lot." Yale Insights: Research, Judith A. Chevalier, April 16, 2019; https://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/gig-workers-value-their-flexibility-lot.

2 O'Callahan, T., ed. "The Unexpected Impacts of Innovation." Yale Insights: Faculty Viewpoints, Judith A. Chevalier, February 28, 2022; https://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/the-unexpected-impacts-of-innovation.

3 Chen, M.K.; Rossi, P.E.; Chevalier, J.A. and Oehlsen, E. "The Value of Flexible Work: Evidence from Uber Drivers." Journal of Political Economy, December 2019, 127(6), pp. 2735-94; https://doi.org/10.1086/702171.

4 O'Callahan, T., ed. 2022. (See footnote 2.)

5 Barrios, J.M.; Hochberg, Y.V. and Yi, H. "Launching with a Parachute: The Gig Economy and New Business Formation." Journal of Financial Economics, April 2022, 144(1), pp. 22-43; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.12.011.

© 2024, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

Glossary

Barriers to entry: Obstacles that make it difficult for a producer to enter a market. Examples might include control of a scarce resource or high fixed or start-up costs.

Gig economy: Labor market that relies on temporary and part-time workers who are often independent contractors and freelancers rather than full-time employees.

Two-sided market: A market where two different groups, usually buyers and sellers, need to be connected by an intermediary.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed