What Should College Athletes Be Paid? Market Structure and the NCAA

"From the start, American colleges and universities have had a

complicated relationship with sports and money."

—Justice Neil Gorsuch, NCAA v. Alston (2021)

Introduction

College athletic programs are an integral part of many college campuses. Colleges earn revenue from ticket sales, merchandise, and licensing agreements. But should the athletes themselves be given a portion of these earnings? There is a long tradition of unpaid amateur athletics in the United States, and many argue that the scholarships offered to student athletes are fair compensation for their time and talent. But recent court cases and subsequent rule changes by bodies governing college athletics have highlighted the underlying market structure of college athletics in the United States—and have begun to change it.

Monopoly vs. Monopsony: What Is the Difference?

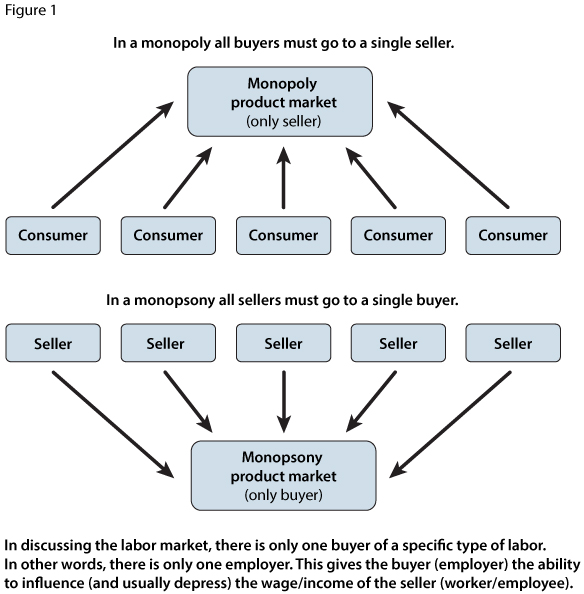

Many of us are familiar with the concept of a monopoly, where a market is controlled by a single firm or producer. Monopolies mean that consumers have no choice when shopping for a product or service, because there is only one supplier. Without competition for buyers, a monopolist can essentially control the market price. Monopolies are generally created when there is some barrier to entry that prevents other producers from joining the market.

But what if, instead of there being only one producer in a market, there was only one consumer? What if you produced a good or service but had only one option when it came time to try and sell your product or service? This is a monopsony (Figure 1).

NCAA As a Monopsony

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) was originally founded to set standards and safety practices for college athletics. Today the NCAA has more than 1,000 member colleges and universities organized into three divisions. Many of the standards and regulations the NCAA established have to do with how member schools can recruit and compensate athletes for participating in college athletics. Colleges and universities are primarily educational institutions, not athletic franchises or companies, so how did the NCAA (and its member schools) end up being defendants in an antitrust claim before the US Supreme Court?

As college athletics increased in popularity, they created more and more revenue for both the NCAA and the colleges and universities. In 2022, the NCAA reportedly earned $1 billion in revenue from March Madness alone.1 The increased revenue the NCAA and member schools received, driven by the increased popularity of college sports, left many questioning if the athletes were still being fairly compensated for their labor.

In 2021, a group of both current and former student athletes filed an antitrust lawsuit against the NCAA (NCAA v. Alston). The Supreme Court ultimately ruled in favor of the students against the NCAA's rules that restricted education-related benefits, such as scholarships for graduate or vocational school or payments for academic tutoring. These types of caps on education-related benefits had kept costs down for member schools who would have otherwise bid up these types of payments to attract potential star athletes.

The US government has several antitrust laws in place that are designed to prevent monopolies from forming and that require competition be maintained in the market. It has been long held in the US that monopolies hurt the consumer by reducing output, raising prices, and limiting innovation. (When producers do not compete, there is less incentive to innovate or lower costs.) The Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890) prohibits "contract[s], combination[s], or conspiracy[ies] in restraint of trade or commerce."2

When a person or group files an antitrust claim, the court must determine if the parties involved are limiting competition in a way that is detrimental to consumers. But would the same reasoning be applied to a monopsony? According to the Supreme Court in the NCAA case, yes.3

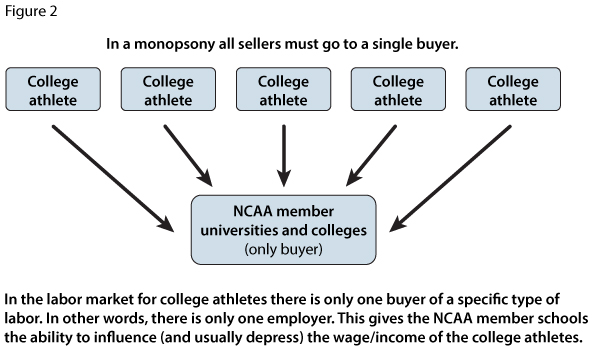

College athletes are in essence "selling" their labor to colleges/universities in exchange for scholarships, tuition, and other education-related expenses. If you are an amateur athlete, there is no other viable "buyer" in this labor market beyond colleges and universities. In short, the NCAA has established a monopsony labor market for amateur athletes (Figure 2).

Because there is no other labor market for these amateur athletes to sell their talent and skills, the NCAA guidelines determine how student athletes are compensated. The Supreme Court found that because member schools compete against each other to recruit student athletes, the NCAA, through rules like limiting education-related benefits, used its monopsony power to "cap artificially the compensation offered to recruits."4

The Court ruled that these caps violate antitrust law, which has opened the door to further debate and rule changes related to student athlete compensation. We are already seeing policy changes that have begun to reduce the monopsony power of the NCAA.

Opening the Door for Name, Image, Likeness

Following the ruling in NCAA v. Alston, the NCAA made a major policy change that has reshaped the way student athletes are compensated for their talent. Starting in July 2021, the NCAA allows all Division I-III student athletes to be compensated for use of their Name, Image, Likeness (NIL). Examples of using NIL include a university selling jerseys with an athlete's name on them or licensing an avatar in an athlete's likeness for a video game.

This change reversed previous policy that strictly forbade college athletes from earning "benefits linked to their participation in a sport."5 That is, colleges and universities could earn income by selling merchandise and licensing featuring an athlete, but the individual would not receive any compensation based on sales of these items. Nor could college athletes participate in any individual endorsement or advertising contracts.

With the new NIL policy, college athletes are now able to accept endorsement deals with both large national brands and smaller local businesses. Big-ticket endorsements can earn players upward of $1 million per year, while smaller sums of money or free products from smaller local businesses are often available for college players.

Long-Term Consequences

Monopsonies are less common and certainly less visible than monopolies; but monopsony labor markets still have a large impact on the income and wages of laborers within those markets. While colleges and universities are not your typical profit-making businesses, and so unique circumstances must be considered, we can see in the college athletics example how monopsony power can depress earnings and compensation for athletes within these markets.

With changes in policies around NIL and education-related compensation for student athletes, the landscape of college sports is changing. NIL has created opportunities for athletes to profit from endorsements and advertising contracts and is already impacting the way colleges recruit, as schools are offering programs and partnerships internally to help student athletes make the most of their NIL opportunities. Less than 2% of NCAA athletes move on to play professional sports; so, the opportunity for NIL compensation during their college years is important for the vast majority of these athletes who may not have similar opportunities in the future.6

While the debate over college athlete compensation goes on, reducing the monopsony power of the NCAA and expanding earnings competition among college athletes will definitely change the way these institutions recruit, manage, promote, and retain athletes. The complex relationship between higher education, sports, and money won't become any less complex anytime soon.

Notes

1 Blinder, Alan and Draper, Kevin. "Topping $1 Billion a Year, Big Ten Signs Record TV Deal for College Conference." New York Times, August 18, 2022; https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/sports/ncaafootball/big-ten-deal-tv.html.

2 The Sherman Anti-Trust Act, July 2, 1890; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-1992; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives.

3 No. 20-512 National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Alston, 2021.

4 NCAA v. Alston, 2021. (See footnote 3.)

5 Blinder and Draper, 2022. (See footnote 1.)

6 National Collegiate Athletic Association. "NCAA Recruiting Fact Sheet." August 2021; https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/compliance/recruiting/NCAA_RecruitingFactSheet.pdf.

© 2023, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

Glossary

Antitrust law: Legislation that prohibits practices that restrain trade, such as price fixing and business arrangements designed to achieve monopoly power.

Barriers to entry: Obstacles that make it difficult for a producer to enter a market. Examples might include control of a scarce resource or high fixed or start-up costs.

Competition: Competition takes place in markets. Sellers compete with other sellers for sales to consumers. Sellers compete on the basis of price, product quality, customer service, product design and variety, and advertising. Buyers compete with other consumers for goods and services. This often results in higher prices.

Incentives: Perceived benefits that encourage certain behaviors.

Market: Buyers and sellers coming together to exchange goods, services, and/or resources.

Monopoly: A market for a good or service where there is only one supplier, or that is dominated by one supplier. Barriers prevent entry to the market and there are no close substitutes for the product.

Monopsony: A market for a good or service where there is only one buyer, or that is dominated by one buyer.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed