Making Sense of the National Debt

"Blessed are the young for they shall inherit the national debt."

—Herbert Hoover

We live in a world of scarcity—which means that our wants exceed the resources required to fulfill them. For many of us, a household budget constrains how many goods and services we can buy. But, what if we want to consume more goods and services than our budget allows? We can borrow against future income to fulfill our wants now.1 This type of spending—when your spending exceeds your income—is called deficit spending. The downside of borrowing money, of course, is that you must repay it with interest, so you will have less money to buy goods and services in the future.

Figure 1

2018 U.S. Federal Deficit

In 2018 the federal deficit was $779 billion, which means that the U.S. federal government spent $779 billion more than it collected.

SOURCE: https://datalab.usaspending.gov/americas-finance-guide/. Data are provided by the U.S. Department of the Treasury and refer to fiscal year 2018.

Governments face the same dilemma. They too can run a deficit, or borrow against future income, to fulfill more of their citizens' wants now (Figure 1). For a variety of reasons, governments may borrow rather than fund spending with current taxes. Deficit spending can be used to invest in infrastructure, education, research and development, and other programs intended to boost future productivity. Because this type of investment can increase productive capacity, it can also increase national income over time. And deficit spending can be used to create demand for goods and services during recessions.

For the U.S. government, deficit spending has become the norm. In the past 90 years, it has run 76 annual deficits and only 14 annual surpluses. In the past 50 years, it has run only 4 annual surpluses.2 The accumulation of past deficits and surpluses is the current national debt: Deficits add to the debt, while surpluses subtract from the debt. At the end of the first quarter of 2019, the total national debt, also called total U.S. federal public debt, was $22 trillion and growing. This circumstance raises important questions: How much debt can an economy sustain? What are the long-term risks of high debt levels?

Who "Owns" the National Debt?

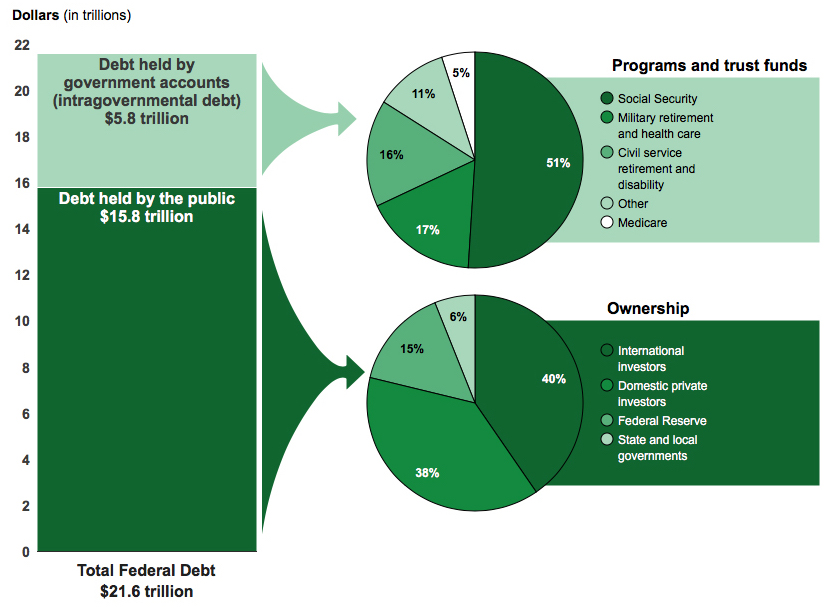

While individuals borrow money from financial institutions, the U.S. federal government borrows by selling U.S. Treasury securities (bills, notes, and bonds) to "the public." For example, when investors purchase newly issued U.S. Treasury securities, they are lending their money to the U.S. government. The purchaser may receive periodic payments and/or a final payment, known as the "face value," at the end of the term. You or someone close to you likely holds U.S. Treasury securities either directly in an investment portfolio or indirectly through a mutual fund or pension account. As such, you, or they, own U.S. government debt. But, as a taxpayer, you are also beholden to pay part of that debt. A majority of the national debt is held by "the public," which includes individuals, corporations, state or local governments, Federal Reserve Banks, and foreign governments.3 In other words, debt held by the public includes U.S. government debt held by any entity except the U.S. federal government itself (Figure 2). The largest public holders of U.S. government debt are international investors (40 percent), domestic private investors (38 percent), Federal Reserve Banks (15 percent), and state and local governments (6 percent).4

Figure 2

Fiscal Year 2018 Debt Held by the Public and Intragovernmental Debt

SOURCE: https://www.gao.gov/americas_fiscal_future?t=federal_debt, accessed September 5, 2019.

In addition to owing money to "the public," the U.S. government also owes money to departments within the U.S. government. For example, the Social Security system has run surpluses for many years (the amount collected through the Social Security tax was greater than the benefits paid out) and placed the money in a trust fund.5 These surpluses were used to purchase U.S. Treasury securities. Forecasts suggest that as the population ages and demographics change, the amount paid in Social Security benefits will exceed the revenues collected through the Social Security tax and the money saved in the trust fund will be needed to fill the gap. In short, some of the $22 trillion in total debt is intragovernmental holdings—money the government owes itself. Of the total national debt, $5.8 trillion is intragovernmental holdings and the remaining $16.2 trillion is debt held by the public.6 Because debt held by the public represents debt payments external to the government, many economists feel it is a better measure of the debt burden.

Household and Government Financing Over the Life Cycle

The life cycle theory of consumption and saving holds that households seek to smooth their consumption of goods and services over the life cycle by borrowing early in life (for college or to buy a home), then saving and paying down debt during their working careers, and finally living on their savings during retirement. Financial advisors often suggest that people try to be debt free before they retire. As such, people are often motivated in their prime working years to pay down their debts and then pay them off entirely before they quit working. Given this mindset, people often assume that government debt must be paid in full at some point. But there are important differences between government debt and household debt.

While people tend to prefer to pay off their debts before they retire (and stop earning income) or die, governments endure indefinitely. In general, governments expect that their economies will continue to grow and that they will continue to collect tax revenue. If governments need to refinance past debts or cover new deficits, they can simply borrow. In effect, governments never need to pay off their debts entirely because the governments will exist indefinitely.

However, this does not mean that debt is without cost. It is important to understand that debt has an opportunity cost. For the 2018 fiscal year, interest payments on the U.S. national debt were $523 billion.7 This money could have financed other projects if the debt did not exist. And, of course, that $523 billion was simply the interest on the existing debt and did not pay down that debt.

How Much Debt Is Too Much Debt?

Although governments may endure indefinitely, that does not mean they can accumulate unlimited debt. Governments must have the necessary income to finance their debt. Economists use gross domestic product (GDP), the total market value, expressed in dollars, of all final goods and services produced in an economy in a given year, as a measure of national income. Because GDP indicates national income, it also indicates the potential income that can be taxed, and taxes are a primary source of government revenues. In this way, a nation's GDP determines how much debt can be supported, which is similar to how a person's income determines how much debt that person can reasonably take on. Just as individuals can sustain higher debt as their incomes increase, economies can sustain higher debt when the economy grows over time. However, if debt grows at a faster rate than income, eventually the debt might become unsustainable. Economists use the debt-to GDP ratio to measure how sustainable the debt is (Figure 3). Some economists, referred to as "owls," suggest that people's worries about U.S. government debt are overblown (see the boxed insert, "Deficit Hawks, Doves, and…Owls?").

Figure 3

Federal Debt Held by the Public as Percent of Gross Domestic Product

Federal debt held by the public has grown faster than GDP, leading to a rising debt-to-GDP ratio.

NOTE: Gray bars indicate recessions as determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

SOURCE: U.S. Office of Management and Budget. FRED®, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=lKfK, accessed September 5, 2019.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) suggests that the U.S government debt is currently on an unsustainable path: The federal debt is projected to grow at a faster rate than GDP for the foreseeable future. A significant portion of the growth in projected debt is to fund social programs such as Medicare and Social Security. Using debt held by the public (instead of total public debt), the debt-to-GDP ratio averaged 46 percent from 1946 to 2018 but reached 77 percent by the end of 2018 (see Figure 3). It is projected to exceed 100 percent within 20 years.8

Debt Risks

Credit risk is the risk to the lender that the borrower will not repay the loan. It is one component of the interest rate that borrowers pay. Like for all loans, interest rates on Treasury securities reflect risk of default. The higher the risk of default, the higher the interest rate investors will expect: A country perceived as a higher credit risk must pay bond holders higher interest rates than a country perceived as a lower credit risk, all else equal. Thus, when bond yields spike, it might reflect rising risk.

Economist Herb Stein once said, "If something cannot go on forever, it will stop." In other words, trends that are unsustainable will not continue because the economy will adjust, sometimes in abrupt and jarring ways. While governments never have to entirely pay off debt, there are debt levels that investors might perceive as unsustainable. A solution some countries with high levels of unsustainable debt have tried is printing money. In this scenario, the government borrows money by issuing bonds and then orders the central bank to buy those bonds by creating (printing) money. History has taught us, however, that this type of policy leads to extremely high rates of inflation (hyperinflation) and often ends in economic ruin. Some of the better-known examples of such polices are Germany in 1921-23, Zimbabwe in 2007-09, and Venezuela currently. An important protection against this type of policy is to create an independent central bank that is insulated from the political process and has clear objectives (such as a specific target for the inflation rate) so that it can make policy decisions to sustain economic health over the long run rather than respond to political pressures.9

Conclusion

The national debt is high by historical standards—and rising. People often assume that governments must pay off their debts in the same way that individuals do. However, there are important differences: Governments (and their economies) do not retire, and governments do not die (or don't intend to). As long as their debt payments remain sustainable, governments can finance their debt indefinitely. And if a government prints money to solve its debt problem, history warns that hyperinflation and financial ruin will likely result. While debt in itself is not a bad thing, it can become dangerous if it becomes unsustainable.

Notes

1 Households could alternately spend out of past savings.

2 U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "Federal Surplus or Deficit." FRED®, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=otZF, accessed September 5, 2019.

3 U.S Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service. "Frequently Asked Questions about the Public Debt." https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/resources/faq/faq_publicdebt.htm#DebtOwner, accessed September 5, 2019.

4 U.S. Government Accountability Office. "America's Fiscal Future: Federal Debt." https://www.gao.gov/americas_fiscal_future?t=federal_debt, accessed September 5, 2019.

5 Social Security Administration. "Trust Fund Data." https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4a3.html, accessed September 5, 2019.

6 U.S. Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service. "Federal Debt Held by the Public." FRED®, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=mAfK, accessed September 5, 2019.

7 U.S Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service. "Interest Expense on the Debt Outstanding." https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/ir/ir_expense.htm, accessed September 5, 2019.

8 U.S. Government Accountability Office. "America's Fiscal Future." https://www.gao.gov/americas_fiscal_future?t=fiscal_forecast#projecting_the_future, accessed September 5, 2019.

9 Waller, Christopher. "Independence + Accountability: Why the Fed Is a Well-Designed Central Bank." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, September/October 2011, 93(5), pp. 293-301; https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/review/11/09/293-302Waller.pdf.

© 2019, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

Glossary

Default: The failure to promptly pay interest or principal when due.

Fiat money: A substance or device used as money, having no intrinsic value (no value of its own), or representational value (not representing anything of value, such as gold).

Hyperinflation: A very rapid rise in the overall price level; an extremely high rate of inflation.

Inflation: A general, sustained upward movement of prices for goods and services in an economy.

National debt: The accumulation of budget deficits. Also known as government debt.

Opportunity cost: The value of the next-best alternative when a decision is made; it's what is given up.

Productive capacity: The maximum output an economy can produce with the current level of available resources.

Scarcity: The condition that exists because there are not enough resources to produce everyone's wants.

U.S. Treasury securities: Bonds, notes, bills, and other debt instruments sold by the U.S. government to finance its expenditures.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed