The Affordable Care Act: More Health Care Services at Lower Cost?

"You would think that would not be so controversial. (Laughter.) You would think people would say, okay, let's go ahead and let's do this so everybody has health insurance coverage. The result is more choice, more competition, real health care security."

—President Obama concerning the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)1

The Affordable Care Act

In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed by Congress and signed by President Obama with two main purposes:

• Provide health insurance to those not currently covered

• Decrease costs across the U.S. health care system2

Figure 1 shows a measure of health care expenditures per person in the United States over the past two decades. In the context of the ACA, the goal of decreasing costs is synonymous with decreasing the expenditures paid by the average consumer for health care—or at least causing expenditures to increase more slowly.

Figure 1

Real Personal Consumption Expenditures on Health Care Services, Per-Person 2012 Dollars

NOTE: The figure does not include net health insurance/worker's compensation, prescription or nonprescription drugs, or medical equipment or supplies classified under nondurable/durable goods. Gray bar indicates recession as determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

SOURCE: FRED®, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=oj4b, accessed August 19, 2019.

How Consumers Pay for Health Care

Expenditures are paid by consumers to doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers in three ways: (i) directly to providers as out-of-pocket payments, (ii) through fees paid to private insurers that then pay providers, and (iii) through taxes paid for government insurance and spending programs such as Medicare and Medicaid that cover provider charges. Estimates for 2019 indicate that at least 44 percent of health insurance costs will be paid privately, either directly by consumers or via private insurance (Table 1).

Expenditures that flow from consumers to providers can be broken down into the following: the quantities and prices of health care goods and services (Expenditure = Quantity × Price), administrative costs of insurers and payment systems, and profits for private insurers. Any legislation that attempts to control total costs has to control quantities, prices, profits, or administrative costs—or some combination of each.

Goal: Improving Coverage

To improve coverage, starting in 2014, the ACA required Americans to purchase insurance and gave two key incentives to do so: (i) Those who do not purchase insurance must pay a tax penalty, and (ii) low-income households and individuals who purchase insurance will receive a monetary subsidy (otherwise known as a rebate) from the federal government. The ACA also created exchanges for firms to sell health insurance plans to newly subsidized households.

Although these key incentives did not take effect until 2014, the law implemented other measures earlier to improve coverage. For example, health insurers may no longer deny coverage based on preexisting health conditions of new enrollees, young adults must be allowed to stay on their parents' coverage through age 26, and employers with 50 or more employees must offer health insurance as part of a benefit plan. According to the Center for Disease Control, the percentage of uninsured decreased from 16 percent of the population in 2010 to 9.1 percent in 2017, with much of the decrease attributed to the ACA.3

Goal: Controlling Costs

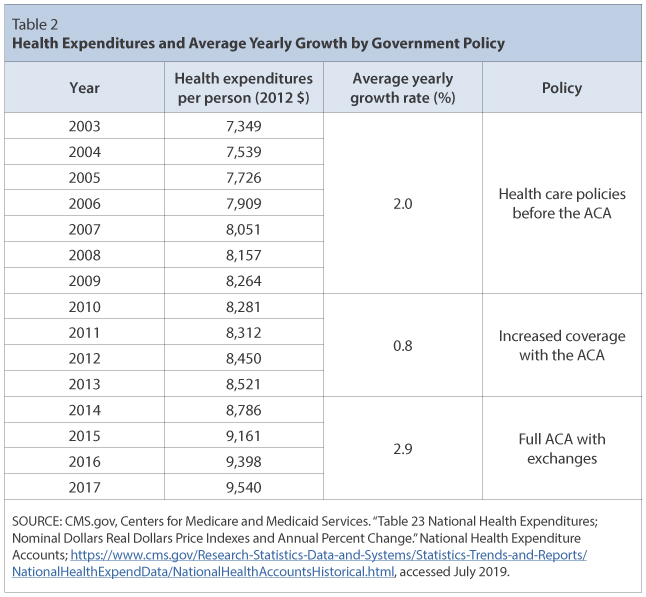

The enactment of the ACA in 2014 did not decrease the per-person costs of health care services; it did not even slow down the rate of increase in costs. As shown in Figure 1, the per-person costs, as measured by expenditures, rose noticeably more rapidly starting in the first quarter of 2014. A broader definition of costs that includes all insurance payments, pharmaceuticals, and medical equipment implies the same result: Per-person costs have increased by 2.9 percent yearly since the ACA was fully enacted compared with 2.0 percent before its passage in 2010 (Table 2). Several factors may help explain why the cost of health care continues to grow, but this article focuses on one—lack of competition.

Market Power and Competition

Discussions of rising health care costs often overlook the role that limited competition in health insurance markets may play. If numerous firms produce identical products, those firms will compete by keeping prices low. In such competitive markets, firms have little to no power to control their prices. If they charge higher prices than their competition, they may get no customers, while if they charge lower prices, they may lose money. At the other end of the spectrum are monopoly markets, where only one firm exists and can set pricing based on its individual costs—because there is no competition. Anyone who has ever seen a movie at their local cinema has viewed a type of monopoly first hand4: The candy counter has the exclusive right to sell their goods in that market and can therefore sell at elevated prices.5 Even companies in markets with very few firms, called oligopolies, will have some power to control pricing. As a general rule of thumb, markets with one or few firms have more market power, which is the ability to control and elevate prices above competitive levels.

There are several ways to measure market power, such as the four-firm concentration ratio and the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). The HHI takes the percentage of the market that each firm possesses, squares each percentage, and then sums the squares. The maximum value of the HHI is 10,000, while the minimum is arbitrarily close to 0. For instance, if one firm has a monopoly in a market, that firm would have 100 percent of the market and the market's HHI would be 10,000:

HHI = 1002 = 10,000 (monopolist).

In contrast, a market with 1,000 firms each possessing 0.1 percent of the market would have an HHI of 10:

HHI = 0.12 + 0.12 + 0.12 + …… (Add 0.12 1,000 times total.) = 1000 * 0.01 = 10.

In general, the higher the HHI, the more likely firms will have market power.

Market Power in ACA Exchanges

In economic theory, competitive markets can reduce costs to consumers by forcing insurance companies to keep prices at competitive levels and forfeit monopoly profits. With similar health insurance requirements and subsidies for low-income households, the Swiss health care system offers a model for comparison with the U.S. health care system. As of 2011, there were close to 100 insurers in Switzerland competing for consumer health care dollars, forcing firms to compete by setting prices to just cover costs.6 In the United States, markets are state specific and consumers may choose from plans available in the state in which they reside. In 2014, of the 50 states and the District of Columbia, 11 had only 1 or 2 insurers, 21 had 3 or 4, and only 19 states had 5 or more.7 As of July 2019, the number of states with only 1 or 2 insurers had increased from 11 to 20, indicating a growing divide between ACA exchanges and competitive markets. Measuring market concentration by HHI yields similar results (Table 3), with 43 percent of markets classified as super concentrated and 47 percent as highly concentrated. Therefore, the ACA has not yet been successful in creating highly competitive markets.

Additionally, researchers have found mounting evidence that the lack of competition in health care exchanges is directly related to premium increases. Jessica Van Parys claims that markets with only one or two insurers see an average increase in consumer premiums of 50 percent.8 Similarly, Richard Scheffler and Daniel Arnold claim that although monopolistic insurers can indeed use their market power to negotiate better prices from health care providers, insurers often keep any savings for themselves in order to increase profits, rather than pass the savings on to consumers.9

Of course, more analysis would be required to determine if the lack of competition is contributing to the ACA not generating the cost savings it is hoped to achieve. There are many other factors to consider, such as expanded benefits and higher government subsidies, that could be keeping costs elevated.

Conclusion

In offering more expansive health care coverage to U.S. citizens under the Affordable Care Act, lawmakers are forced to face the question of whether such coverage is driving up costs. With low-income consumers receiving new subsidies to pay for health insurance, and with insurers having to cover new patients with preexisting conditions that often require expensive treatment, one should expect that more services would lead to higher costs. Economic theory suggests that increasing the level of competition in the insurance market could decrease monopolistic practices and reduce costs to consumers. Based on market concentration data, the United States seems to have a long way to go to substantially increase competition among insurers.

Notes

1 The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. "Remarks by the President on the Affordable Care Act." Press Release, September 26, 2013; https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2013/09/26/remarks-president-affordable-care-act.

2 HealthCare.gov. "The Affordable Care Act." Glossary; https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/affordable-care-act/, accessed August 2019.

3 Cohen, Robin A.; Terlizzi; Emily P. and Martinez. Michael E. "Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2018." U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Health Center for Statistics, May 2019; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201905.pdf.

4 While a theatre's movie tickets and candy combined could face competition from other theatres in town, the candy counter has a monopoly within its own theatre.

5 Even monopolies don't charge arbitrarily high prices; instead, monopolists choose prices to maximize their profits. A higher price would mean higher profits on each product but fewer customers.

6 Roy, Avik. "Why Switzerland Has the World's Best Health Care System." Forbes, April 29, 2011; https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2011/04/29/why-switzerland-has-the-worlds-best-health-care-system/#2416d9a67d74.

7 Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. "Number of Issuers Participating in the Individual Health Insurance Marketplaces." State Health Facts; https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/number-of-issuers-participating-in-the-individual-health-insurance-marketplace, accessed July 2019.

8 Van Parys, Jessica. "ACA Marketplace Premiums Grew More Rapidly in Areas with Monopoly Insurers than in Areas with More Competition." Health Affairs, August 2018, 37(8), pp. 1243-51.

9 Scheffler, Richard M. and Arnold, Daniel R. "Insurer Market Power Lowers Prices in Numerous Concentrated Provider Markets." Health Affairs, September 2017, 36(9), pp. 1539-46.

© 2019, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

Glossary

Competitive markets: Markets in which there are many buyers and many sellers so that each has a negligible impact on market prices.

Exchanges (noun): Institutions established for buyers and sellers to trade goods, services, resources, and/or money.

Expenditures: Money spent to buy goods and services.

Four-firm concentration ratio: The market share held by the four largest firms in an industry. Larger concentration ratios generally indicate less competition. The maximum value for concentration ratios is 100%.

Health insurance: Insurance that pays for medical and surgical expenses incurred by the insured.

Market power: The ability of a single economic agent (or small group of agents) to have a substantial influence on market prices.

Monopoly: A market for a good or a service where there is only one supplier or that is dominated by one supplier. Barriers prevent entry to the market, and there are no close substitutes for the product.

Oligopoly: A market for a good or a service where there are very few suppliers or that is dominated by few suppliers. Barriers prevent entry to the market, and there are few close substitutes for the product.

Profit: The amount of revenue that remains after a business pays the costs of producing a good or service.

Subsidy: A payment made by the government to support a business or market. No good or service is provided to the government in return for the payment.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed