Bad Medicine? Federal Debt and Deficits after COVID-19

In January 2020, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the federal budget deficit (a negative surplus) would total $1.015 trillion in fiscal year (FY) 2020 and $1 trillion in FY 2021.1 Those projections are now obsolete because of the many actions taken by government officials to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. These actions, while designed to prevent a health crisis of an unknown magnitude and duration, have nonetheless helped trigger massive job losses and the shuttering of businesses. A deep recession is likely. The deep recession will further increase the size of the federal budget deficit since lower economic activity will reduce tax revenues and automatically increase certain types of federal expenditures (e.g., unemployment benefits).

As in the 2008 Financial Crisis, fiscal policymakers (Congress and the Administration) have responded aggressively to help mitigate the economic damage wrought by the collapse in economic activity. This spring, several pieces of legislation were signed into law. The largest is the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act—or CARES Act—which was signed into law on March 27.2 The Act is effectively two main parts. The first is a $1.8 trillion package that, according to the CBO, increases mandatory outlays by nearly $1 trillion; decreases federal tax revenue by $408 billion; and increases discretionary outlays by about $325 billion.3

The second major part of the CARES Act authorizes the Secretary of the Treasury to provide up to $454 billion to fund emergency lending facilities established by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. A follow-up round of spending was approved on April 24, when President Trump signed the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act (PPPHCA) into law. This Act adds additional funding for the Paycheck Protection Program, among other things. The price tag for the PPPHCA is about $483 billion.

All told, enacted legislation thus far provides about $2.75 trillion in tax relief, spending authority, grants, and other actions to offset the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. This increased spending has occurred through increased issuance of debt by the Treasury, a large percentage of which has been purchased by the Federal Reserve.4

The government's response to stem the pandemic has resulted in an erosion in public finances. This is worrisome because it is occurring against the backdrop of the ongoing retirement of the Baby Boom generation that, according to CBO projections, will see the debt-to-GDP ratio rise to never-before-seen levels in U.S. history.

Federal Deficits: Actual and Projected

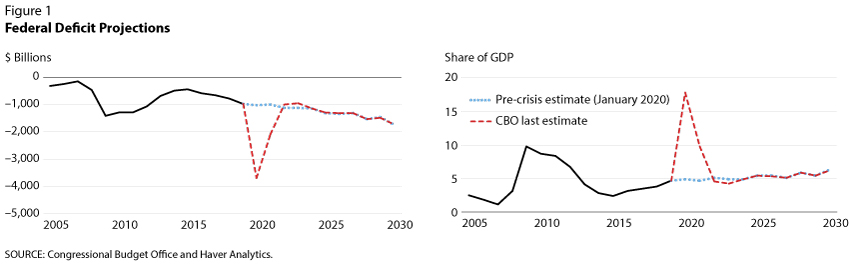

Figure 1 plots the actual and projected federal budget deficits as a percent of nominal GDP from 2005 to 2030. This essay focuses on the unified budget deficit, which is the sum of on- and off-budget deficits and surpluses. One could alternatively look at primary deficits/surpluses; primary deficits exclude interest payments on outstanding debt held by the public.5

The blue dotted line is the CBO's pre-pandemic January 2020 baseline projections.6 The other projection plotted in Figure 1 is based on the latest estimates for FY 2020 and FY 2021 reported in an April 24 CBO blog entry. This April projection includes the estimated effects of the two aforementioned pandemic-related laws passed on March 27 and April 24, as well as two earlier pieces of legislation passed on March 4 and March 18.7 Importantly, the latest CBO projection also includes the economic effects from the likely deep economic contraction in real GDP. The CBO projects that real GDP will decline by 5.6 percent between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the fourth quarter of 2020. If realized, this year's decline would be the largest since real GDP fell by 11.6 percent in 1946.8

In the January 2020 baseline, the federal deficit was projected to total about $1 trillion in FY 2020 and FY 2021. As seen in Figure 1, these deficits amounted to a projected 4.9 percent of nominal GDP in FY 2020 and 4.7 percent in FY 2021. The deficit-to-GDP ratio was projected to increase to 6.3 percent of nominal GDP in FY 2030.

In response to the pandemic-related legislation, the CBO now projects that the budget deficit in FY 2020 will be $3.7 trillion—more than three times larger than the January baseline. As seen in Figure 1, this year's deficit is projected to total nearly 18 percent of GDP; this deficit would be the largest since 1945 (21 percent).9 The deficit is expected to decline (in absolute terms) to $2.1 trillion in FY 2021, which would be about 10 percent of GDP.10 Based on the CBO's April 24 projections, the deficits effectively return to earlier baseline levels beginning in 2024. But whereas the deficit as a share of GDP returns relatively quickly to the pre-pandemic projections, the accumulation of federal debt permanently increases publicly-held debt as a share of GDP.11

Federal Debt: Actual and Projected

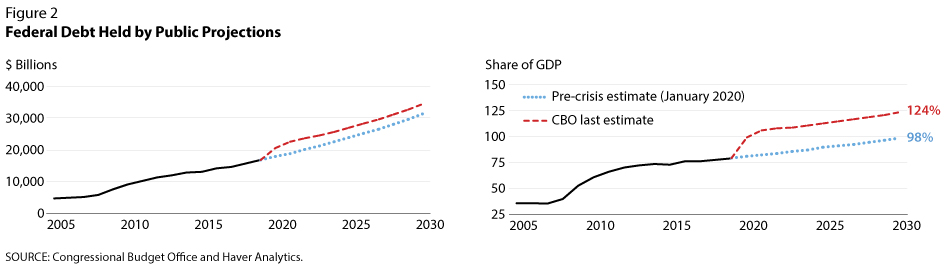

Figure 2 shows actual and projected federal debt held by the public over the same period as in Figure 1.12 In the January 2020 CBO baseline, federal debt was projected to increase from $16.8 trillion (79.2 percent of GDP) in FY 2019 to nearly $31.5 trillion by FY 2030 (98.3 percent of projected GDP). This projection is shown by the dotted line in Figure 2.

The second projection in Figure 2, the dashed line, is the debt-to-GDP ratio that accounts for the pandemic legislation and the likely sharp decline in real GDP in 2020. The sharp fall in real GDP over the short run magnifies the increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio. Based on the CBO's April update, debt held by the public increases from $20.5 trillion in FY 2020 (99 percent of GDP) to about $34.4 trillion in 2030 (124 percent of GDP). Essentially, there is a one-time upward shift in both the level of debt in dollar terms and debt as a share of GDP. Importantly, after accounting for the deep recession and pandemic-related federal spending and tax-cut programs, debt as a share of GDP in FY 2030 is now projected to be 25.4 percentage points more than that projected in the January 2020 baseline.

If the projections in Figure 2 are realized, the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio will greatly surpass the previous record of 106 percent set in 1946. According to its long-term budget projections published in January 2020, the CBO estimated that federal debt as a percentage of GDP would increase to 180 percent by 2050. However, updating the long-run projections to account for the pandemic-spawned spending and deep recession would result in a projected debt-to-GDP level of 227 percent in 2050. If realized, this would be about six and a half times larger than the debt-to-GDP level that prevailed in 2007 before the Financial Crisis.

It is important to note some caveats about debt and deficit projections. First, as Kliesen and Thornton (2012) showed, deficit and debt projection errors as a share of GDP are large over longer horizons. Indeed, the CBO reported in 2019 that an analysis of historical debt projections showed that the baseline debt projection at the end of the sixth year has a two-thirds chance of being within 8.6 percent of GDP; that is, 8.6 percent above or below the baseline projection that assumes no changes to current laws affecting spending or revenues. Statistically, error bands tend to widen the farther one forecasts into the future. Second, the current low-interest rate environment mitigates the debt burden. Still, in its January baseline projections, the CBO projects that net interest as a share of GDP is expected to increase from 1.7 percent in FY 2020 to 2.6 percent in 2030.

Conclusion

The combination of pandemic legislation and the projected deep recession this year has resulted in a stunning erosion in federal finances. The sharp increase in deficits and debt also has potentially dire implications for the long-term U.S. fiscal outlook. This essay has not discussed the possible economic costs and benefits of such an increase in debt of this magnitude. Others have weighed in on this issue.13

Notes

1 CBO-projected federal budget deficits would average $1.31 trillion during FY 2021 to 2030.

2 The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis maintains a timeline of key COVID-19-related events and policy actions. See https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/timeline/covid-19-pandemic.

3 See "Letter to the Honorable Mike Enzi: Preliminary Estimate of the Effects of H.R. 748, the CARES Act, Public Law 116-136, Revised, With Corrections to the Revenue Effect of the Employee Retention Credit and to the Modification of a Limitation on Losses for Taxpayers Other than Corporations," April 27, 2020.

4 See Martin, Fernando. "The Impact of the Fed's Response So Far." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Preliminary Essay, May 2020; https://research.stlouisfed.org/resources/covid-19/preliminary/impact-fed-response-so-far.

5 See Martin (2012).

6 The CBO released updated "Baseline Budget Projections" on March 6. They are based on the economic forecast reported in the January 2020 Budget and Economic Outlook but include legislation enacted through March 6—one of which was pandemic related. The dollar difference between the January and March baseline is trivial.

7 See https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56335.

8 On May 19, the CBO released updated economic projections for 2020 and 2021. It predicts that real GDP will decline by 5.6 percent in 2020, the same as reported in the April 24 projections. See: https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2020-05/56351-CBO-interim-projections.pdf.

9 Martin (2012) shows that the federal primary deficit was much larger during WWII—roughly 27 percent in 1943.

10 Nominal GDP is projected to increase by 3 percent per year from FY 2021 to 2022.

11 The assumption of a permanent increase in debt is based on the continuation of current tax and expenditure laws.

12 Martin's essay "The Impact of the Fed's Response So Far" (see footnote 4) shows that the lion's share of debt held by the public has been purchased by the Federal Reserve as part of its policy response this year.

13 See Blanchard (2019) and Boskin (2020).

References

Blanchard, Olivier. "Public Debt and Low Interest Rates." American Economic Review, 2019, 109(4), pp. 1197-1229; https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.109.4.1197.

Boskin, Michael J. "Are Large Deficits and Debt Dangerous?" National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 26727, February 2020; https://www.nber.org/papers/w26727.

Congressional Budget Office. "An Evaluation of CBO's Past Deficit and Debt Projections." Congress of the United States, Congressional Budget Office, September 2019; https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-09/55234-CBO-deficits-debts.pdf.

Kliesen, Kevin. L. and Thornton, Daniel L. "How Good Are the Government's Deficit and Debt Projections and Should We Care?" Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 2012, 94(1), pp. 21-39; https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/2012/01/01/how-good-are-the-governments-deficit-and-debt-projections-and-should-we-care.

Martin, Fernando M. "Government Policy Response to War-Expenditure Shocks." B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, 2012, 12(1), pp. 2011-28.

© 2020, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed