Fed Intervention in the To-Be-Announced Market for Mortgage-Backed Securities

A complex web of lending and financial transactions supports the housing market. Of these, the most fundamental is the mortgage, a loan to buy a house. To understand the mortgage market, it is necessary to understand the process of securitizing mortgages and guaranteeing their payments. When Americans borrow to buy a house, the lending bank or thrift usually sells the right to receive the mortgage payments to one of two government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), called Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.1 The federal government took over these formerly private corporations during the financial crisis. The GSEs issue bonds with implicit government guarantees, and they form mortgage pools with the capital. These agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) transfer interest and principal payments from residential mortgages back to investors. This process, known as securitization, potentially allows investors to diversify and control their exposure to risk, consequently allowing borrowers to pay lower interest rates. Securitization takes small, heterogeneous securities (mortgages) and creates larger, more-diversified, more-homogeneous securities that are more easily traded at lower cost. The agency share of securitization is greater than 97 percent (Housing Finance Policy Center, 2020). The to-be-announced (TBA) market is a forward market for these agency MBS. More than 90 percent of the trading in mortgage securities takes place in the TBA market (Vickery and Wright, 2013).

Ginnie Mae is a government agency, part of the Department of Housing and Urban Development. It has a more limited role than Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in that it does not issue MBS but only guarantees that the MBS will make timely payments even in the case of borrower default on federally insured or guaranteed loans.2 An important difference between Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae is that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac sell MBS securitized from conventional mortgages, while Ginnie Mae's guarantees are disproportionately to historically underserved communities and low-income borrowers.

Figure 1

Pending Home Sales

SOURCE: Redfin.

The coronavirus-related financial turmoil discussed in our essay on equity markets and the corporate bond market has also affected the housing markets. According to data from Redfin, a national real estate brokerage, pending home sales slowed significantly during late February as bad news about the coronavirus accumulated and the stock market turned down (Figure 1). Pending sales then fell 42 percent in March as the virus disrupted economic and social relations. Great uncertainty about the state of the economy substantially raised risk premia in March, and yields on risky assets, such as high-yield bonds, soared; and even yields on traditionally safe AAA bonds increased for a time as well. Figure 2 shows that the declines in long-term Treasury yields may have sped up after mid-February, as bad news about the virus spread and the stock market declined. Figure 2 shows that 30-year mortgage rates shared these patterns, including a large spike upward due to widespread liquidity problems on March 19.

As housing finance markets shared the liquidity problems created by COVID-19, the Federal Reserve chose to intervene in the dominant market for MBS, the TBA market. On March 15 the FOMC announced that it would buy at least $500 billion in Treasury securities and at least $200 billion in agency MBS. A Fed statement further specified that it would concentrate on recently produced coupons in 30-year and 15-year fixed-rate agency MBS in the TBA market. The FOMC expanded these purchases on March 20 and then made them open ended on March 23, with the goal of ensuring smooth functioning of markets. All the announced MBS purchases are designed to provide liquidity and facilitate trading of agency MBS during a period of disruption associated with the coronavirus.

The two panels of Figure 3 illustrate the volume and number of the Fed's recent TBA purchases, respectively. Through April 7, the New York Fed's Open Market Trading Desk (the Desk) has purchased a total of $407 billion in TBA in 36 different securities. The highest rate of purchases was from March 20 through March 27.

Figure 4 illustrates the effect of such interventions on a common measure of liquidity, the bid-ask spread for agency MBS in the TBA market. Because Ginnie Mae-guaranteed securities are less liquid, they have higher bid-ask spreads than those of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The spreads for both types of securities went up sharply from late February to early March. Ginnie Mae spreads went from a typical value of $0.10 in late February to $0.20 to $0.35 by the second week of March, while spreads on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac MBS similarly increased from $0.03 to a range of about $0.10 to $0.20 over the same span of time. Both sets of spreads substantially declined again during the Fed's large MBS purchases during the week of March 23 to March 27, indicating greater liquidity.

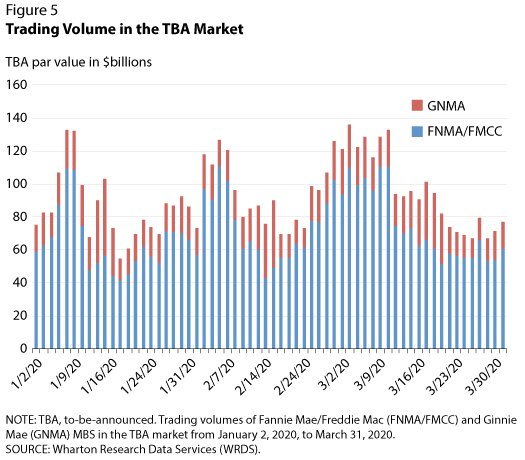

Figure 5 shows that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac TBA trading volume initially rose as bid-ask spreads soared but declined substantially before the Fed's big interventions from March 20 to March 27. From March 2 to March 13, average daily volume was $94.3 billion. From March 16 to March 31, average volume fell 38 percent to $58.3 billion.

While the Federal Reserve's actions have stabilized the housing finance market for the moment, the health of the broader economy will ultimately determine the behavior of trading activity, transactions costs, and issuance of mortgage-backed securities.

Notes

1 The Federal Housing Finance Agency supervises Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. Fannie Mae was established in 1938 as the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA) to buy Federal Housing Administration mortgages, and it was privatized in 1968. The government established Freddie Mac in 1970 as the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC with a ticker of FMCC). Freddie Mac was supposed to compete with Fannie Mae and was allowed to buy a wider variety of mortgages.

2 Federal agencies that insure mortgages include the Federal Housing Administration, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development, and the Office of Public and Indian Housing.

References

Housing Finance Policy Center. "Housing Finance at a Glance: A Monthly Chartbook." At a Glance, February 2020; https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/101766/february20chartbook202020.pdf.

Vickery, James and Joshua Wright. "TBA Trading and Liquidity in the Agency MBS Market," Economic Policy Review, 19(1), 2013; https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/epr/2013/1212vick.pdf.

© 2020, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed