Married Men Sit Atop the Wage Ladder

Data show that the average male worker earns a higher wage than the average female worker. Figure 1 illustrates this: It plots the wage and salary income of men and women, by age. The sample represented here includes all men and women employed in 2016 with at least a high school diploma.

A few details are worth pointing out with this figure. First, wages tend to increase with age—at least up until age 50. This is presumably because people accumulate human capital as they work and, therefore, become more productive. Second, for both men and women, there is a tendency for wages to decrease in the latter years of their working lives—that is, after age 50. This is probably because, by then, workers devote less effort to accumulating new human capital. Finally, the salary difference between men and women is noticeably less pronounced earlier in life rather than later in life.

It is tempting to ascribe this latter point to the fact that younger women are more likely to get married, have children, and eventually withdraw from the labor force. Once out of the labor force, these women would not accumulate human capital, and, subsequently, they would lose ground relative to men. This would explain why the difference in wages grows with age.

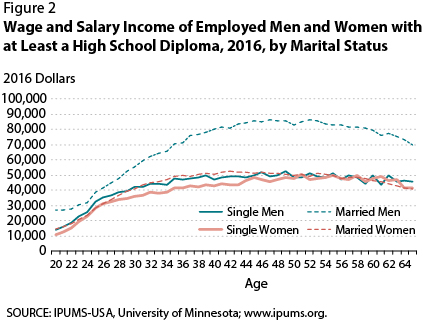

Figure 2 offers a decomposition of the data in Figure 1 that questions this theory. It plots the wage and salary income of workers with at least a high school diploma by age, gender, and marital status. Figure 2 presents many striking features. First, there are almost no gender differences in wages among single (that is, never-married) workers: Whether they are men or women, single workers earn very similar wages. Second, married and single women also earn similar wages. This is surprising since married women may be more likely to have children than single women. Thus, this second point is not consistent with the view that the gender wage gap results from women having children earlier in life and losing ground in human capital accumulation relative to men. Finally, married men earn wages that dominate those of the other three categories; that is, married men earn higher wages than single or married women, and married men earn higher wages than single men.

The data in Figure 2 do not imply that being married increases a man's wage. It might be that men with higher wages are more likely to marry; therefore, the average married man earns a higher wage than the average single man.

Men often marry later than women, so there are relatively few married men in their 20s. This explains why, in Figure 1, the difference in wages is less pronounced earlier in life: The average male worker in his 20s is more likely single than married.

The gender wage gap remains a complicated topic. But progress may come from asking different questions: not just why women earn less than men (although not compared with single men), but also why married men earn so much more than everyone else.

© 2018, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed