On Corporate Income Taxes, Employment, and Wages

The passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 has resulted in debate on whether the decline in personal and corporate income tax rates will increase employment, income, and wages. Terms relating to the legal forms that firms organize under, such as C corporations and pass-through firms, have been mentioned. In this essay, we discuss how the legal form of a firm relates to the outcomes of the new tax law.

In a recent paper with Daphne Chen, we examined whether a decline in the corporate income tax rate could increase employment and wages.1 We found that decreasing the corporate income tax rate from 28 percent to 20 percent in our model would eventually lead to a 1.3 percent increase in output, a 3.3 percent decline in the unemployment rate, and a slight increase in wealth inequality. One of the important factors, often ignored in the debate, is the way a business legally organizes. Here we explain alternative ways a business can legally organize as well as which organizational forms are the most dominant in the United States. The relative importance of the organizational forms plays an important role in determining whether a decline in the corporate income tax rate will stimulate output and employment. These lessons are used to evaluate the 2012 income tax reform in the state of Kansas and the recent Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

An individual who decides to start a firm must decide how to legally organize the firm.2 The choice usually is between a C corporation or a pass-through firm. The C-corporate legal form is subject to a business income tax, and any after-tax distribution to individual owners is subject to the personal income tax. This double taxation is an unattractive feature of the C-corporate legal form. In contrast, pass-through firms are subject only to the personal income tax. However, pass-through firms face legal limitations on their ability to raise financing beyond the owners' individual funds. For example, in an S corporation, the number of shareholders cannot exceed 100, and shareholders must be individual U.S. citizens, not corporations.

Table 1 presents the relative percentages of the various legal forms of organization according to tax filings, net income, and labor statistics. Based on tax data for 2012, 95 percent of firms that filed taxes did not pay the corporate income tax. This is explained by the fact that most firms are classified as pass-through entities and file under the personal income tax. However, the C-corporate form accounts for 41 percent of net income, suggesting these firms tend to be large.3 From a labor market perspective, pass-through firms account for 57 percent of employment, with the S-corporate form accounting for nearly half of the pass-through share. However, in terms of labor payroll expenses, the C-corporate form accounts for 62 percent of the total. Of the pass-through entities, the S-corporate form accounts for the majority of the payroll share.

How does the legal organization of firms impact how a change in the corporate income tax influences output and employment? A decline in the corporate income tax reduces the cost of double taxation for C corporations—even with the personal income tax rate unchanged. Because pass-through firms tend to have more difficulty accessing outside financing, if the costs of double taxation are reduced to where the benefits from being able to access outside financing dominate, pass-through firms will switch their legal form of organization to a C corporation. The combined benefit of lower taxation and enhanced access to capital can increase output and employment.

Changes in the personal income tax could also have an effect on C corporations, as such changes affect the impact of double taxation. For example, in 2012 the state of Kansas reformed its personal income tax code—with the goal of stimulating state employment and output—and reduced personal income tax rates (Table 2).4 In addition, non-wage income of pass-through firms became exempt from taxation. No change was made to the corporate income tax. At the time of passage, the Governor's Office of the state of Kansas issued the following statement: "Dynamic projections show the new law will result in 22,900 new jobs [and] give $2 billion more in disposable income to Kansans."5 What was the result of this policy change? By 2016, the Kansas economy had not grown faster than those of neighboring states. In addition, many firms switched to the pass-through legal form from the C-corporate legal form, the state's bond ratings fell, and primary central services such as education had to be decreased. We examined a similar policy change in our simulation framework. The results were similar to what actually happened in Kansas. Why? The policy change incentivized some C corporations to switch to the pass-through form to take advantage of the tax exemption on non-wage income. Hence, firms switched their legal form of organization, but not to the C-corporate form. As a result, highly productive firms that switched from the C-corporate legal form reduced their ability to access outside financial capital and thus employment and output did not increase.

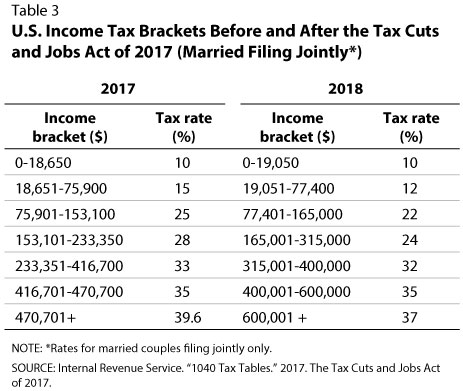

This past December, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act substantially revised the federal personal and business income tax codes. Prior to 2018, C corporations faced eight income tax brackets, with statutory tax rates ranging from 15 to 38 percent. Under the new law, the corporate income tax rate is lowered to 21 percent for all C corporations. Table 3 compares the tax brackets and corresponding tax rates for 2017 and 2018. Pass-through firms are impacted by the new legislation in two ways: (i) statutory tax rates declined and (ii) 20 percent of their taxable income is deductible.6

An obvious question is whether the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act will increase employment and output. The decline in the statutory corporate tax rate is substantial, making the C-corporate legal form potentially more attractive to pass-through entities. However, personal income tax rates have been reduced, coupled with many pass-through firms being able to deduct 20 percent of their income. The combined effect is a reduction in the personal income tax liability of pass-through firms. It is not obvious that pass-through firms have the incentive to reorganize as a C corporation with possible improved access to capital that eventually results in employment and output growth. Because of the size of the decline in the corporate tax rate as well as how the act impacts the way equipment and structures costs are deducted for tax purposes, C corporations may decide to increase investment, leading to output and employment gains. We are currently studying the implications of the entire new policy.

Notes

1 Chen, Daphne; Qi, Shi and Schlagenhauf, Don. "Corporate Income Taxes, Legal Form of Organization and Employment." American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics (forthcoming). This paper was originally published as Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2017-021A; https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/wp/2017/2017-021.pdf.

2 A pass-through firm can organize in a number of ways, such as an S corporation, a partnership, or a sole proprietorship.

3 Not all large firms are C corporations, however. Large pass-through firms include Cargill, Enterprise Holdings, Hobby Lobby, Koch Industries, and Publix Super Markets.

4 Table 2 shows the changes for married couples filing jointly only. The tax code was also changed for single individuals and married couples filing separately.

5 Behlmann, Emily. "Kansas Tax Cuts Signed Into Law." Wichita Business Journal. May 22, 2012; https://www.bizjournals.com/wichita/news/2012/05/22/kansas-tax-cuts-signed-into-law.html.

6 In our discussion of the new tax code, we focus on the changes in the statutory tax rates. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act includes many other changes, such as indexing the brackets to the chained consumer price index for all urban consumers, allowing 100 percent expensing of investment in equipment, and shortening the length of time over which structures can be depreciated.

© 2018, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed