The Rising Federal Funds Rate in the Current Low Long-Term Interest Rate Environment

After keeping the federal funds rate close to zero for seven years, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) increased its target rate by 25 basis points in December 2015. Additional 25-basis-point hikes followed in December 2016, March 2017, and June 2017, putting the rate at 1.0 to 1.25 percent. Clearly, the FOMC has initiated a new rate-hike cycle, and it is likely that the federal funds rate will rise further. According to the latest projections of FOMC participants, one more rate hike is expected this year, which would lift the federal funds rate by another 25 basis points.

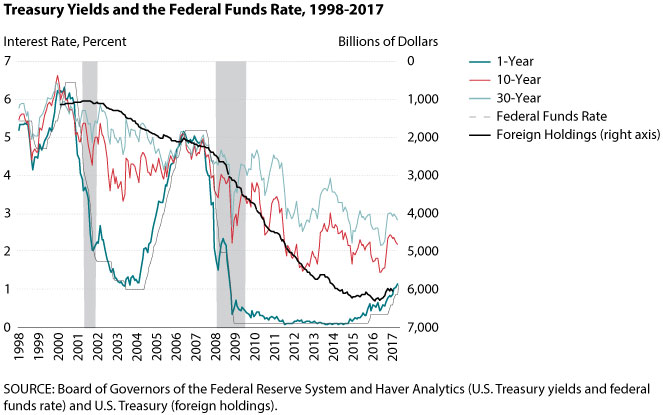

The thin black line in the figure plots the federal funds rate from 1998 to now. The federal funds rate, which is the overnight borrowing rate among commercial banks, varied significantly before the financial crisis, peaking at 6.5 percent in 2000 and dropping rapidly to 1.25 percent in response to the 2001 recession. The Federal Reserve started raising the rate in the second quarter of 2004 and quickly pushed it to 5.25 percent, where it stayed until right before the financial crisis. After the financial crisis, the federal funds rate remained low until the end of 2015.

Is it likely that the federal funds rate will reach the heights seen in the previous cycles? If not, how high might it go? Let's start by examining the long-term interest rate (the light blue line in the figure), which is commonly measured by the 30-year Treasury yield. Even with considerable movement in the federal funds rate, the 30-year long-term yield declined consistently over the sample period, from around 6 to 7 percent in the late 1990s to around just 3 percent today. This slow decline suggests that the low long-term yield is not a result of the close-to-zero federal funds rate that held from 2009 to 2015. The increasing foreign demand for U.S. government bonds is likely an important contributing factor to the decline of the long-term yield. The thick black line, using an inverted scale, shows the foreign holdings of U.S. Treasury securities. Foreigners have increased their holdings of U.S. Treasury securities sixfold, from around $1 trillion in 2000 to more than $6 trillion in 2017. As the foreign demand for Treasuries increases, the price of Treasury securities goes up and the yield goes down. Thus, the decline in long-term interest rates likely has more to do with increasing foreign demand for Treasury securities than federal funds rate policy.

The figure also shows the 1-year (dark blue line) and 10-year (red line) Treasury yields. The 1-year Treasury yield follows the federal funds rate more closely than the long-term 10- and 30-year rates. The interest rate differential between the federal funds rate and the 1-year Treasury yield has been small throughout the period. This is not surprising given that the federal funds rate is a very short-term interest rate. Overnight interest rates should be more closely related to the short-term Treasury yields than to the long-term yields. In other words, the influence of the federal funds rate on Treasury yields diminishes with maturity. The federal funds rate strongly influences short-term yields, but this influence gets weaker as the maturity increases. Going forward, it is unlikely that the long-term rate will increase as much as the federal funds rate.

So how high might the federal funds rate go? The low long-term yield might affect the FOMC's decisionmaking on the federal funds rate target. If a series of rate hikes were to increase short-term rates, with little change in long-term rates, short-term rates could surpass long-term rates. This phenomenon is referred to as the inverted yield curve and is believed to be a strong indicator of recessions. It occurred before the 2001 and 2007-09 recessions, as shown in the figure. The Federal Reserve quickly responded in each instance by dropping the federal funds rate target, explaining why the federal funds rate did not exceed the long-term yield by a large margin for extended periods. Hence, it is unreasonable to expect the federal funds rate to reach 5 or 6 percent during the current rate-hike cycle because of the low long-term yield. The projections of the federal funds rate for the next few years seem to be consistent with this discussion. The median projection of FOMC participants is 2.1 percent and 2.9 percent by the end of 2018 and 2019, respectively, which is close to the long-term yield.1 Using federal funds rate futures, the market's prediction of the federal funds rate is even lower for the same periods—only 1.5 percent and 1.65 percent, respectively.2

Notes

1 FOMC. "Economic Projections of Federal Reserve Board Members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents Under Their Individual Assessments of Projected Appropriate Monetary Policy." June 2017; https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20170614.pdf.

2 Bloomberg as of June 26, 2017.

© 2017, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed