What Could We Have Expected from a $10 Minimum Wage in the City of St. Louis?

At the forefront of many debates in the region are the lines that divide us: Missouri and Illinois, St. Louis City and St. Louis County, St. Louis County and St. Charles County, and the list goes on. While these boundaries play a key role in how officials are elected and how government services are provided, they are significantly less important when making regional economic policy. Why? People are generally free to decide where they want to live and work.

For those of us crossing a bridge each day on our journey to work, we are acutely aware of these decisions about where to work and where to live. But despite our best efforts for more regional economic integration and more discussion of regional economic policies, we often lack a genuine understanding of these economic linkages. The recent increase in St. Louis's minimum wage to $10 per hour and likely reversal by the state of Missouri provide an excellent example of how worker commuting patterns play a significant role in understanding who is most impacted by such a policy.1 (Hint: It is not the residents.)

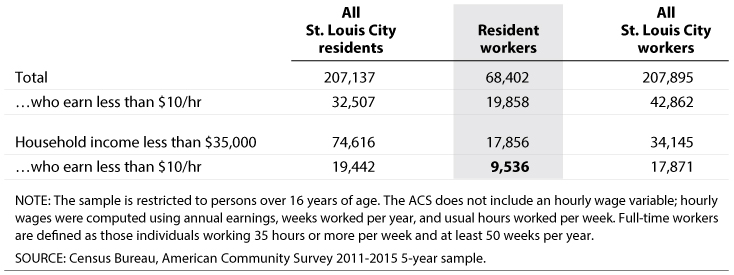

The change in city policy would have directly impacted the entire metropolitan area. Why? Only one-third of the workers in St. Louis City are city residents. While that share rises as wages decline, less than half of the city workers earning less than $10 per hour are residents (see top panel of table). In fact, over a few thousand workers travel across the Mississippi River each day from Illinois for a job paying less than $10 per hour. Instead of raising the wages for about 32,500 city residents that earn under $10 per hour, a city minimum wage raises wages for about 19,900 residents and 23,000 non-residents. But this isn't the end of the story.

The objective of a higher minimum wage is typically to reduce poverty. However, another distinction should be made: There is a difference between low-wage workers and low-income households. More than half of those living in poverty have no one in their household who is employed.2 Moreover, many minimum wage workers are often young workers taking their first job. So, low wages may not be associated with low household income. Of the 19,900 city residents expected to see a raise to $10 per hour, 9,500, or 48 percent, live in households that earn below the median income of about $35,000 (see bottom panel of table). If we look only at full-time workers, this number drops to around 4,800, or 2.3 percent, of all city residents.

Raising the city minimum wage is intended to strengthen the safety net for those roughly 74,600 residents in the bottom half of the income distribution. In practice, the policy works more like a big fishing net, pulling up less than 10,000 targeted residents, while over three-quarters of those that receive a pay increase are neither residents or from low-income households.

Understanding the distinction between residents and workers and low wages and low incomes is an important aspect for policymakers of any city to consider when evaluating a local minimum wage. There are other policies that may be better suited for achieving their objectives of helping low-income residents.3 There is a large economics literature noting the benefits of higher wages, which includes attracting higher-productivity workers to an area: So a local policy may encourage residents currently working outside the city to seek jobs closer to where they live.4

Notes

1 St. Louis and Missouri are not the first to debate local minimum wages. The Economic Policy Institute identifies 32 municipalities with minimum wages above the state minimum wage; http://www.epi.org/minimum-wage-tracker/. At the same time, almost half of state legislatures have worked on legislation to prohibit local minimum wages.

2 For further discussion, see Neumark's "Reducing Poverty via Minimum Wages, Alternatives," Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter, 2015-38; http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2015/december/reducing-poverty-via-minimum-wages-tax-credit/.

3 For example, Neumark (2015) proposes that earned income tax credits are more effective at reducing poverty, as they are likely to increase employment. Policies to improve housing affordability would be more targeted toward residents than workers.

4 For a summary, see Wolfers and Zilinsky's "Higher Wages for Low-Income Workers Lead to Higher Productivity"; https://piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/higher-wages-low-income-workers-lead-higher-productivity.

© 2017, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed