The Heterogeneous Impacts of Rising Inflation

Recent data show an upward trend in the inflation rate, as measured by the consumer price index (CPI). The CPI is a measure of the average change over time in the prices urban consumers pay for a market basket of consumer goods and services. CPI is thus regarded as a measure of the cost of living of an average American.

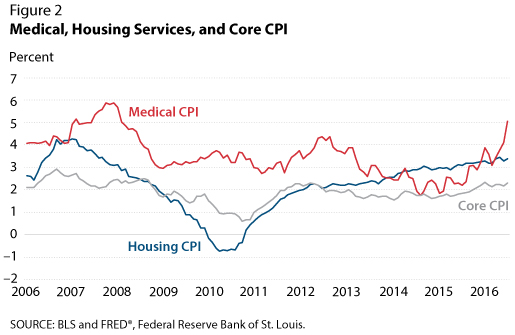

According to the CPI, the inflation rate was near zero at the beginning of 2015 and gradually increased to 1.1 percent in August of this year, with a recent peak of 1.3 percent in January. Short-term movement of the CPI can be driven by changes in food and energy prices, which tend to be volatile. To avoid this bias, another measure, core CPI, excludes food and energy prices. Over the past two years, core CPI also increased, from 1.6 percent at the beginning of 2015 to 2.3 percent this August. Figure 1 shows the movement in these series over the past 10 years. It is clear that overall CPI is much more volatile than core CPI.

Because consumption decisions vary from person to person, very few Americans consume the average market basket measured by the CPI. Increases in the inflation rates for certain goods and services will have larger effects on some persons than others. For example, relative to core CPI, increases in the inflation rates for shelter and medical services have been significant. Given the large share of consumption devoted to these two services, this essay explores how increases in year-over-year inflation rates are likely to affect certain groups more than others.

Housing services (shelter) represent roughly 20 percent of average annual expenditures, a significant amount of most budgets.1 As shown in Figure 2, prices of housing services have been increasing, hitting a post- recession peak of 3.5 percent in June 2016. The impact of these increases, however, has been different for renters and homeowners. The BLS defines shelter as the service that housing provides, rather than the housing itself. For renters, the cost of shelter is rent paid. There is, however, no market price for homeowner housing services. To account for the cost of shelter for homeowners, the BLS calculates implicit rent; that is, it defines the cost as what the owner occupants would pay if they were renting their homes.2 Since the cost of rent is implicit, it has no direct effect on daily income or expenses. As a result, the inflationary pressures associated with housing services directly affect renters but not existing homeowners.

The homeownership rate is the share of households that own their housing. The Census Bureau calculates homeownership rates by age, race and ethnicity, and income.3 As of the second quarter of 2015, the overall rate stands at approximately 63 percent, indicating that over a third of American households currently rent. In addition, certain subsets of the population are more likely to own homes than others. Homeownership rates steadily increase with age, rising with each age bracket. While around one-third of those under 35 years of age are homeowners, the rate jumps to nearly 80 percent for those over 65. In terms of race and ethnicity, the homeownership rate for whites is significantly higher than those for blacks and Hispanics. Lastly, for households with income greater than or equal to the median, the homeownership rate is close to 80 percent, while for households with income below the median it stands at less than 50 percent. In summary, young people, minorities, and lower-income households are more likely to rent and thus are more likely to be affected by an increase in the inflation rate of housing services.

The inflation rate of medical services affects subsets of the population differently as well. The rate increased from 1.8 percent in February 2015 to 5.1 percent this August. Medical services represent nearly 8 percent of average annual expenditures, so the impact of the increase could be significant. Alemayehu and Warner (2004) find that medical expenditures typically increase with age, with nearly half of lifetime medical expenditures occurring after 65 years of age. In addition, health insurance coverage has a significant impact on how much individuals spend on medical services. For those without health insurance, rising costs directly correlate with out-of-pocket medical expenditures. And the cost increases could be significant relative to total income.

The national uninsured rate was over 10 percent in 2014, with minorities, lower-income individuals, and individuals in their 20s and 30s most likely to be uninsured,4 making them the hardest hit by rising medical costs. Those with health insurance, however, may be affected as well. Insurance premiums are likely to increase as the prices of medical services rise. For those with government or employer-sponsored health insurance, the increase may not be large relative to total income. However, for those who purchase health insurance individually, it could be. Relative to housing services, the effects of rising medical services are more complex.

The current inflation rate is modest from a historical perspective. The CPI and core CPI inflation rates are still lower than before the 2007 recession, as is the inflation rate for housing (3.4 percent). The inflation rate for medical services (5.1 percent) is higher than its pre-recession level. Inflation has been on an upward trend recently; and if inflation rates continue to pick up, the increases are likely to impact various subsets of the population more than others.5

Notes

1 Expenditures data are from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer Expenditure Survey; http://www.bls.gov/news.release/cesan.nr0.htm.

2 For more information on how the BLS calculates implicit rent, see http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpifacnewrent.pdf.

3 For the homeownership rate and the rates by age, race and ethnicity, and income, see http://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/files/currenthvspress.pdf.

4 For the uninsured rate and the rates by race and ethnicity and income, see http://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/visualizations/p60/253/figure6.pdf. For the uninsured rate by age, see http://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/visualizations/p60/253/figure4.pdf.

5 To estimate your personal CPI, check out the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta myCPI tool at https://www.frbatlanta.org/research/inflationproject/mycpi.aspx.

Reference

Alemayehu, Berhanu and Warner, Kenneth E. "The Lifetime Distribution of Health Care Costs." Health Services Research, June 2004, 39(3), pp. 627-42.

© 2016, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed