Russia’s Demographic Problems Started Before the Collapse of the Soviet Union

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, Russia's gross domestic product declined by more than 5 percent per year for 10 years, its birth rate sharply declined, and its death rate peaked. The timing of these events has led to the popular view that the collapse of the Soviet Union either caused or revealed challenges facing the Russian economy. Some of Russia's alarming demographic trends, however, were already in place before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

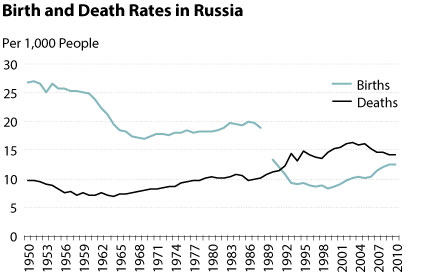

The figure shows Russia's birth and death rates since 1950. The birth rate declined steadily throughout the 1950s and 1960s before leveling off. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, the birth rate declined sharply before leveling off again in the second half of the 1990s. Around the turn of the century, it started to rise. The death rate slightly declined during the 1950s and then rose from the mid-1960s until the early 2000s before declining slightly again.

NOTE: The gap in the data corresponds to the period immediately following the fall of the Soviet Union.

SOURCE: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. (ed.). International Historical Statistics. April 2013; http://www.palgraveconnect.com/pc/doifinder/10.1057/9781137305688.0001.

Economic theory might explain the changes in Russia's birth rate. For example, better economic opportunities—that is, higher wages—for potential parents can reduce birth rates: Young adults may decide that the opportunity cost of raising a child is too high and therefore amend their plans to have children. Like good conditions, bad conditions can also reduce birth rates, but for different reasons.

In the case of Russia, better economic opportunities might have reduced the birth rate during the 1950s and 1960s. Harrison (1993) reports that the Soviet Union's most rapid post-World War II growth occurred during the 1950s and 1960s.1 Bad economic prospects and uncertainty—long observed to lead people to have fewer children—explain the later collapse in the birth rate. Prominent, albeit extreme, examples of such phenomena can be found during almost every war and/or conflict.2

In contrast, the behavior of Russia's death rate is remarkable and more difficult to explain. Most countries experienced declining death rates throughout the twentieth century—but not Russia. What may be even more remarkable is that its death rate began to increase in the 1960s—predating the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Researchers do know that far more alcohol-related deaths occur in Russia than in any other country.3 This phenomenon is not new: It dates back at least to the Tsarist era but has recently worsened.4 Does an increase in alcohol-related deaths in Russia explain the upward trend in its death rate since the 1960s? And why is alcoholism so prevalent in Russia? The answers to these questions are not obvious. Treisman (2010), for instance, insists the decrease in the relative price of "cheap" alcohol in the early 1990s promoted alcoholism; but again, why was mortality already on the rise? The answers to this and related questions are elusive.

A well-known study by Anne Case and Angus Deaton (2015) shows a similar, but much less extreme, phenomenon in the United States.5 The midlife (45 to 54 years of age) mortality of non-Hispanic white Americans has increased markedly since the late 1990s. Alcohol poisoning, suicide, and diseases associated with drug and alcohol abuse largely explain this increase, which is a unique phenomenon—it is not experienced by any other demographic group or country. Case and Deaton cannot explain the phenomenon. They venture that increasing economic insecurity is a possible culprit, but more studies are needed to figure out what is happening to non-Hispanic white Americans. The answer may help in understanding what has been happening in Russia over the past 50 years.

Historically, the dramatic decline in the birth rate in Russia after the fall of the Berlin Wall was not unusual given the circumstances. The increase in mortality, however, although difficult to explain, began 30 years before the fall of the Soviet Union.

Notes

1 Harrison, Mark. "Soviet Economic Growth since 1928: The Alternative Statistics of G. I. Khanin." Europe-Asia Studies, 1993, 45(1), pp. 141-67; http://www.jstor.org/stable/153253?src=esr&item=10&returnArticleService=showFullText&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

2 See Caldwell, John C. "Social Upheaval and Fertility Decline." Journal of Family History, October 2004, 29(4), pp. 382-406; http://jfh.sagepub.com/content/29/4/382.short.

3 See, for instance, Treisman, Daniel. "Death and Prices: The Political Economy of Russia's Alcohol Crisis." Economics of Transition, April 2010, 18(2), pp. 281-331; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228344450_Death_and_prices_The_political_economy_of_Russia's_alcohol_crisis.

4 See Andreev, Evgeny; Bogoyavlensky, Dmitry and Stickley, Andrew. "Comparing Alcohol Mortality in Tsarist and Contemporary Russia: Is the Current Situation Historically Unique?" Alcohol and Alcoholism, January 2013, 48(2), pp. 215-21; http://alcalc.oxfordjournals.org/content/alcalc/48/2/215.full.pdf.

5 Case, Anne and Deaton, Angus. "Rising Morbidity and Mortality in Midlife Among White Non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st Century." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, December 2015, 112(49), pp. 15078-83; http://www.pnas.org/content/112/49/15078.full?sid=b368ca76-5863-417d-84f1-1cb5e1194a23.

© 2016, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed