Forward Guidance 101B: A Roadmap of the International Experience

Forward guidance is a communication tool that allows central banks to convey their future monetary policy actions, conditional on their evaluation of the economic outlook. We explained in Contessi and Li (2013) the economic rationale of this policy, as well as its different types and the experience with forward guidance in the United States. The Federal Reserve is just one of several central banks that have adopted forward guidance since the beginning of the financial crisis and in an environment of near-zero policy rates (zero lower bound). Others include the Bank of Canada, Bank of England (BOE), the Czech National Bank, and the European Central Bank (ECB). In 1999, Japan became the first major central bank to adopt policy statement language that would become fairly typical of forward guidance when the policy rate was also near zero.

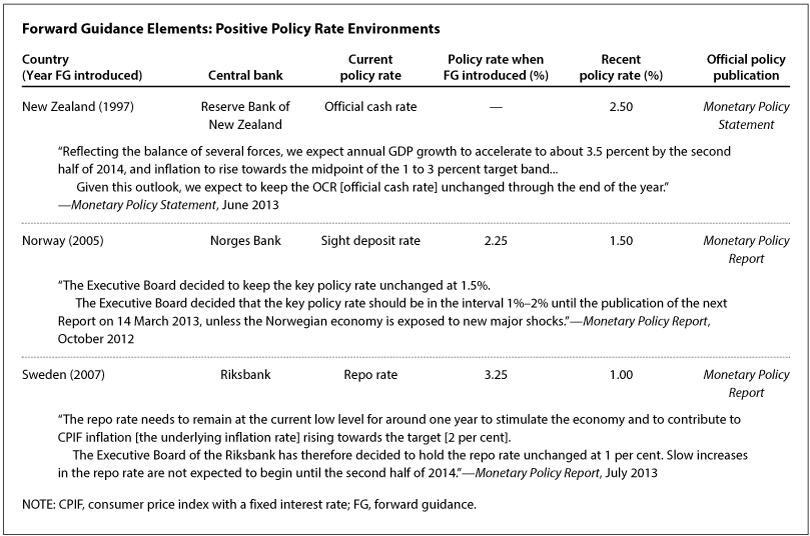

In addition to the recent adoption of forward guidance by these central banks, other inflation-targeting banks have adopted forward guidance in an environment without the zero lower bound. These banks, typically in small, open economies, include those in New Zealand, Norway, and Sweden (Andersson and Hoffman, 2009; Kool and Thornton, 2012). We synthetize the experience of both groups of countries depending on whether they adopted forward guidance during times of conventional monetary policy with policy rates above zero (see the first table) or when the policy rate was near zero (see the second table).

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) has the longest history of providing forward guidance about future monetary policy. The RBNZ began publishing a path for its monetary condition index and forecast for the inflation rate in December 1997.1 The RBNZ explicitly discusses its (i) policy rate (since 1999, the official cash rate, the rate on overnight loans to commercial banks) path and (ii) projections of output and inflation through its Monetary Policy Statement (see the first table). These published projections are model based but incorporate judgmental adjustments and are published without confidence or uncertainty bands. During the post-financial-crisis period, when the policy rate was already as low as 2.5 percent, the RBNZ stated that the official rate would be "unchanged through the end of the year" to reaffirm the public's expectation about the future path of the policy rate (RBNZ Monetary Policy Statement, June 2013, p. 2).

The central bank of Norway, the Norges Bank, adopted forward guidance in 2005 and until recently was the most explicit among current practitioners because its target criterion involves real variables—output and employment—as well as inflation. In its triannual Monetary Policy Report, the bank openly discusses the criteria for an appropriate interest rate path to anchor expectations of low and stable inflation (Norges Bank, 2007, see p. 13). These published projections cover up to three years ahead, but, unlike the RBNZ's projections, they include confidence bands.

Sweden's Riksbank also uses very similar explicit forward guidance. Since 2007, the Riksbank has published its inflation target and forecasts of its policy rate (the repo rate) in its Monetary Policy Report. These reports provide fan charts of the evolution of the policy rate, inflation, and output that illustrate the main economic scenario together with uncertainty bands, allowing for alternative policy paths.

Since the global financial crisis began, the number of inflation-targeting central banks adopting forward guidance as a policy tool has grown. However, unlike the situation for the previous three central banks, policy rates were then at or close to the zero lower bound (see the second table) and central banks were seeking additional accommodation not achievable by lowering their policy rate further, typically in combination with asset purchase programs. The historical precedent to this situation was provided by Japan in the 1999-2001 period.

The new wave of forward guidance adoption started with the United States in the fall of 2008 but continued in April 2009, when Canada's policy rate was close to zero (0.25 percent) and then-Governor Mark Carney2 announced that the target overnight rate would remain at that level until the end of 2010:Q2, which we previously defined as date-based Odyssean forward guidance (Contessi and Li, 2013). The overnight rate then remained unchanged until June 2010, confirming the Bank of Canada's commitment to the announced future course of action.

In July and August 2013, respectively, the ECB and the BOE also adopted forward guidance. While the ECB used the "extended period of time" formulation with no date-based forward guidance, the BOE adopted a quite unprecedented formulation. In July 2013, Governor Carney initially announced that the BOE was considering "the case for adopting some form of forward guidance, including the possible use of intermediate thresholds" (BOE, 2013b). The implementation of forward guidance in the United Kingdom is particularly interesting in its detail: The August Inflation Report news release clarifies that "the MPC [Monetary Policy Committee] intends not to raise Bank Rate from its current level of 0.5% at least until the…unemployment rate has fallen to a threshold of 7%" (BOE, 2013a), subject to very detailed conditions regarding consumer price index inflation 18 to 24 months ahead, medium-term inflation expectations, and threats to financial stability.

The many discussions on the effectiveness of forward guidance and how to measure its effectiveness are beyond the scope of this essay; interested readers are directed to the references. While there is some agreement that central banks' statements can affect long-term interest rates more at the zero lower bound than during conventional times, there has been little research and evidence is currently mixed regarding periods of near-zero policy rates, in which the direct impact of communication changes is potentially more difficult to measure because of other confounding factors. As Woodford (2013) points out, these are also periods in which output and inflation may be particularly sensitive to changes in private sector expectations about macroeconomic conditions once the lower bound no longer prevents the central bank from achieving its normal stabilization objectives.

Forward guidance conveys information not only about a central bank's future policy reaction, but also its projections of output and inflation (International Monetary Fund, 2013). Therefore, empirical studies face the difficult task of distinguishing changes in expectations of the future policy rate related to changes in beliefs about the central bank's policy function from those related to expectations of economic conditions.

Notes

1 The Monetary Conditions Index is a weighted sum of the 90-day bank bill rate and the trade-weighted exchange rate index.

2 Mark Carney was appointed Governor of the Bank of Canada effective February 1, 2008, and departed June 1, 2013. He is currently Governor of the Bank of England; his appointment was effective July 1, 2013.

References

Andersson, Magnus and Hofmann, Boris. "Gauging the Effectiveness of Quantitative Forward Guidance: Evidence from Three Inflation Targets." European Central Bank Working Paper No. 1098, October 2009; http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1098.....

Bank of England. "Bank of England Provides Explicit Guidance Regarding the Future Conduct of Monetary Policy." News release, August 1, 2013a; http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/....

Bank of England. News release, July 4, 2013b; http://www.bankofBOEengland.co.uk/publications/Pag....

Carney, Mark. "Quarterly Inflation Report Q&A." Bank of England press conference transcript, August 7, 2013; http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/ Documents/inflationreport/2013/conf070813.pdf.

Contessi, Silvio and Li, Li. "Forward Guidance 101A: A Roadmap of the U.S. Experience." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Synopses, 2013, No. 25, September 10, 2013; http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/es/13/....

Draghi, Mario. "Introductory Statement to the Press Conference (with Q&A)." European Central Bank, Frankfurt, Germany, July 4, 2013; http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2013/html....

International Monetary Fund. "Unconventional Monetary Policies—Recent Experience and Prospects." April 18, 2013; http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2013/041813a....

Kool, Clemens J.M. and Thornton, Daniel L. "How Effective Is Central Bank Forward Guidance?" Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper No. 2012-063A, December 2012; http://research.stlouisfed.org/wp/2012/2012-063.pd....

Norges Bank. Monetary Policy Report. No. 1, 2007, March 2007; http://www.norges-bank.no/Upload/60834/EN/mpr-01-0....

Reserve Bank of New Zealand. Monetary Policy Statement. June 2013; http://www.rbnz.govt.nz/monetary_policy/monetary_p... jun13.pdf.

Woodford, Michael. "Forward Guidance by Inflation-Targeting Central Banks." Working paper, Columbia University, May 27, 2013; http://www.columbia.edu/~mw2230/RiksbankIT.pdf.

© 2013, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed