Political Pressure on the Bank of Japan: Interference or Accountability?

On January 22, 2013, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) announced that it would raise its target inflation rate from 1 percent to 2 percent, bowing to pressure from Shinzo Abe, Japan's newly elected prime minister. Abe had campaigned on a platform that advocated "unlimited easing" of monetary policy, and the BOJ appears to have already reacted to the new political environment: In addition to the new inflation target, the BOJ expanded its asset purchase program on December 20, 2012, just four days after Abe's election. On January 22, 2013, it announced its intention to coordinate with the government on new policies. Such overt political pressure on a central bank is unusual in developed countries.

To avoid politically motivated interference in day-to-day policy decisions, central banks in developed nations normally operate with a fair degree of independence from the government, which research indicates helps to promote price stability (Alesina and Summers, 1993). Elected governments do, however, normally determine the longer-term goals of central banks and hold central bankers accountable—in some fashion—for achieving those goals. In the United States, for example, the Congress has given the Federal Reserve a dual mandate to achieve stable prices and maximum sustainable employment but leaves it to the Federal Reserve to choose how to accomplish these goals.

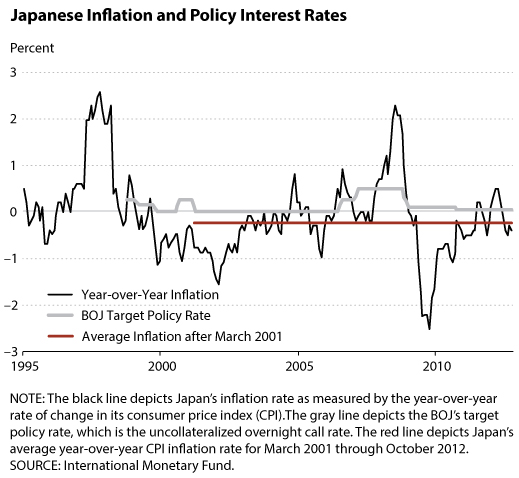

The imposition of a new and higher inflation target has emerged because the BOJ has consistently undershot its own stated goal of stable and positive inflation. On March 19, 2001, the BOJ committed to asset purchases to achieve a policy of stable, nonnegative inflation. The chart shows that Japan has instead endured about 15 years of nearly uninterrupted mild deflation, coupled with zero or near-zero short-term interest rates. Many observers fear that such deflation might hinder economic activity because it establishes a floor on the real rate of interest (the nominal interest rate less expected inflation). Such a floor lowers investment and consumption relative to the levels that would prevail if inflation and interest rates were positive.

Why has the BOJ not raised inflation to positive levels? One possibility is great fear of overshooting the inflation goal. Another possibility is that the BOJ has not tried very hard because it lacks faith in its own monetary instruments. Indeed, there are good reasons to doubt the ability of purely conventional monetary operations—swapping short-term government securities for cash—to stimulate an economy in such a situation because short-term interest rates cannot be lowered further. There are, however, less conventional options for avoiding a deflationary liquidity trap, such as purchasing long-term assets or foreign exchange or the reduction of interest paid on reserves held at the central bank. In any case, the persistent gap between stated intentions and inflation outcomes has undercut the ability of the BOJ to shape the public's expectations, which is vital to successful monetary policy.

Some evidence suggests that markets' expectations for Japanese inflation have gradually increased over the past few months: Since Abe's nomination in September 2012 to January 23, 2013, the Japanese yen has gradually depreciated about 14 percent against the U.S. dollar. While other explanations are certainly possible, this depreciation is consistent with the idea that markets have come to believe that the BOJ can and will raise the inflation rate.

Reference

Alesina, Alberto and Summers, Lawrence H. "Central Bank Independence and Macroeconomic Performance: Some Comparative Evidence." Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, May 1993, 25(2), pp. 151-162.

© 2013, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed