The Sovereign Wealth Funds of Nations

Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are commonly defined as investment vehicles created by government entities to invest in income-producing assets. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), governments use SWFs to (i) stabilize revenues from commodity exports; (ii) invest foreign exchange reserves; (iii) fund pension liabilities and development projects; and (iv) save proceeds from the sale of nonrenewable resources (e.g., oil) for future generations. (This last objective is the most common.)

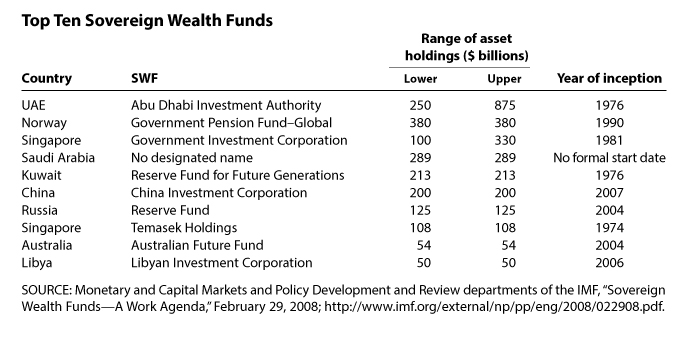

SWFs have been around for many years: For example, the Kuwait Investment Office—which manages funds for the Kuwait Investment Authority—was created in 1953. However, the recent growth in their assets and numbers—and especially their large investments in companies such as Citigroup, Merrill Lynch, and Union Bank of Switzerland—has attracted much new attention. The IMF estimates that SWFs now control $2 to $3 trillion in investments and could have $6 to $10 trillion by 2013. In comparison, in 2006, the market capitalization of all the equity markets in the world was about $50 trillion and world GDP was about $48 trillion. Both the recent hikes in oil prices and the tendency of nations to accumulate foreign exchange reserves have contributed to the growth of SWF assets.

What is the economic logic of SWFs? SWFs permit nations with temporarily high incomes from nonrenewable resources—such as oil exports—to save for the future. That people prefer relatively smooth levels of consumption—rather than starving one year and gorging the next—is a cornerstone of economic theory. SWFs enable governments to save high current income for future spending when income may be lower.

The chart shows that six of the top ten SWFs, measured by asset holdings, come from oil-exporting nations: United Arab Emirates, Norway, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Russia, and Libya. SWFs will enable these countries to maintain their consumption levels after the depletion of their oil, just as 401Ks allow people to save for consumption during their retirement. Likewise, the Australia Futures Fund is intended to save current budget surpluses for expected liabilities in health care and pensions.

From a consumption-smoothing perspective, the rationale for the Chinese SWF (China Investment Corporation or CIC) is opaque. China is still a relatively poor but rapidly growing country, with a large SWF. Essentially, China saves today (reduces consumption) to consume even more in the future, when China will be richer. This is puzzling behavior.

From a mechanical point of view, China's foreign exchange intervention strategy produced the CIC's assets as a byproduct. To restrain the rise of their currency's value, the Chinese State Administration for Foreign Exchange has long purchased foreign currency (by selling their own). Ordinarily, this intervention would raise the Chinese money supply, producing domestic inflation, but the People's Bank of China issues securities (bills) to soak up the excess liquidity created by this foreign exchange intervention. The ultimate outcome is that the Chinese government exchanges its own bonds for foreign assets.

But this mechanical explanation fails to answer the question why China accumulates foreign assets, rather than consuming more or even investing more in domestic physical assets? One might conjecture that China's high savings rate reflects what economists call "precautionary saving"—saving against a downturn—which in turn reflects its relatively recent experience with poverty. Nevertheless, it seems likely that China will not accumulate assets at its present pace forever.

© 2008, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed